Cosa Nostra AG

Apr 16, 2015 • Cecilia Anesi, Giulio Rubino

Isolated and alone in only a few square metres. All around are white walls. There is nobody to talk with. Nobody to write to. Correspondence with the external world is forbidden. No emails, no Facebook. Not even hand-written letters. Just silence. Slowly, you go mad. Even the 'hour of air' is spent alone. For if these men manage to communicate with the outside and get orders to the 'family', assets and people can disappear.

So, this is how Italy’s mafia bosses do time: the 41bis. And this is how Vito Roberto Palazzolo will face the next eight years in Milan prison. But Palazzolo still has a game to play. From his tiny cell he stayed silent for a year-and-a-half. But he is a ticking bomb, and it is only a matter of time before he divulges his secrets - secrets which can undermine entire states security and the balance of power.

Palazzolo spent his adult lifetime as one the most reliable cashiers and savvy investors for the Sicilian Mafia, the Cosa Nostra, and over 20 years evading justice and getting rich beyond imagination.

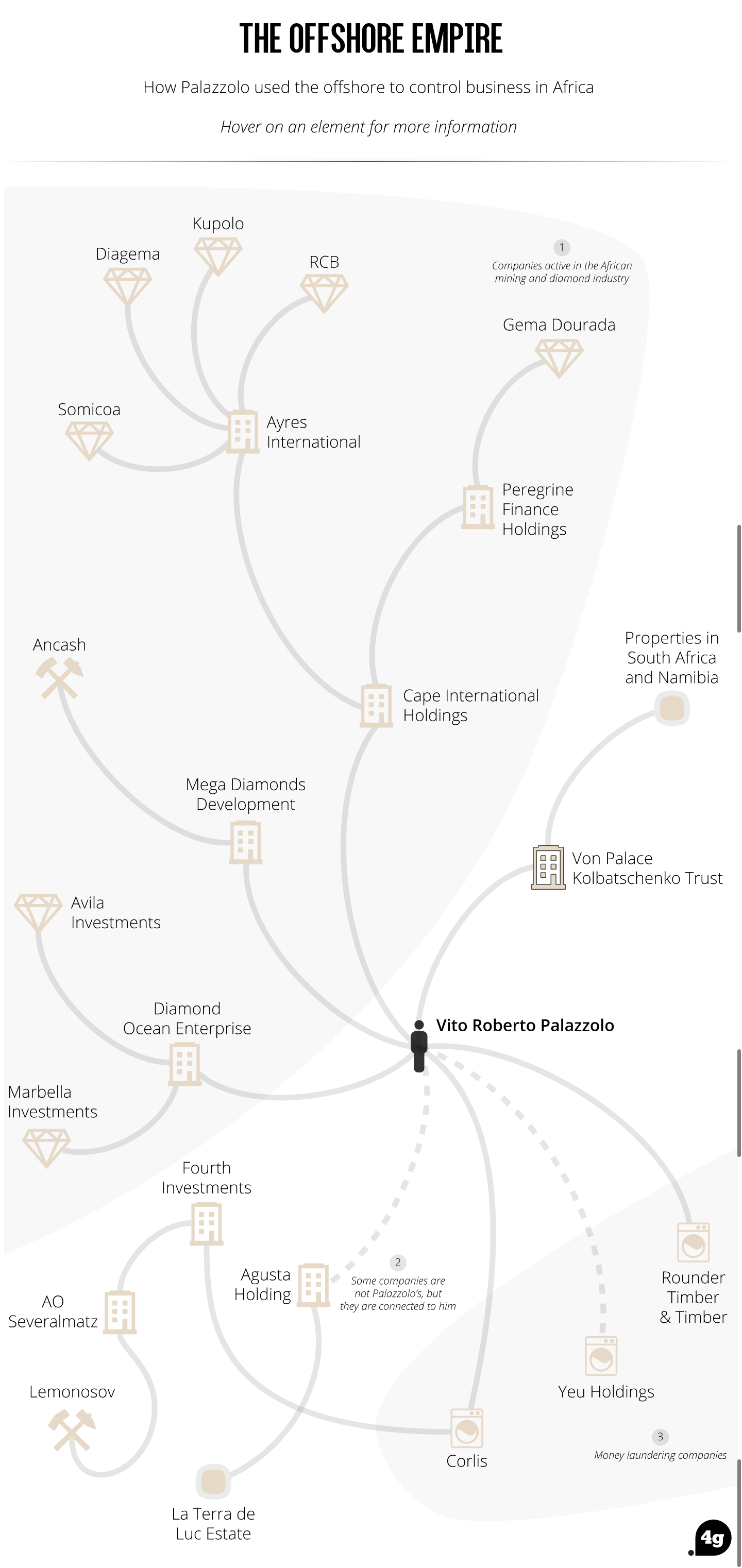

He sits on an empire of gold, diamonds, luxurious properties and billions stashed offshore. He has an army of proxies securing all assets from confiscation. Yet, the most valuable possession is the information he keeps locked in his brain, information regarded by the Sicilian prosecutors as crucial even beyond mafia, as it involves state officials and powerful businessmen.

Palazzolo can still bargain. Anything he wants. He can reveal things that might shake Italy to its core, with the aftershock felt in Germany, Switzerland, the USA and the whole African continent. This is because Palazzolo, in all of these countries, worked his way to the top, influencing political and economical power, in some cases at the very highest levels.

The former mafia banker was convicted in March 2009, after the Italian High court reinforced a 2006 verdict from a Palermo judge. South Africa, where he escaped to from Italy in 1986, refused to extradite him: Mafia association is not a crime there.

Italian authorities only managed to snatch Palazzolo in March 2012 after Interpol apprehended him passing through Thailand.

Extradited, Palazzolo said he was ready to collaborate on “facts until 1984”, in exchange for a softer jail regime. But Prosecutors wanted answers to questions he was not ready for, and Palazzolo fell silent.

One-and-a-half years under 41bis conditions changed his mind. At the end of 2014, Palazzolo decided to talk, although content of his conversations with prosecutors is a secret.

But there is one clue as to the potential direction of the conversations. The prosecutors now interviewing Palazzolo are also assigned to the “Trattativa-stato-mafia” investigation. The “Trattativa-stato-mafia”, literally “treaty between mafia and the State”, is the alleged secret agreement negotiated between 1992 and 1993 among high-ranking Italian officials, politicians and the Cosa Nostra.

When the 41 bis jail regime was introduced the mafia fought back with all of its firepower. Judges Falcone and Borsellino were executed with explosives, and the Cosa Nostra threatened more many more will meet the same fate. The state blinked first. Secret talks began, and three-hundred 41bis jail-terms were cancelled.

But the Cosa Nostra had learned that open war with the state is not the only way to increase its power. There is another side to the mafia, a smart one, a white-collar way. It was in this realm that Palazzolo operated. For thirty years he, with the Cosa Nostra, grew out of control, cutting deals with governments, corporations and other mobsters.

For the first time, a joint investigation by non-profit investigative reporting centres, IRPI, Italy, ANCIR, South Africa and Correct!v, Germany, with the collaboration of the data analysists of Quattrogatti, UK, reveals the extent of Palazzolo’s reach into society and economy.

The New Mafia

Vito Roberto Palazzolo brought the Sicilian mafia into the new century. His skills and contacts made it possible for the Corleonesi clan, undisputed leaders of the Cosa Nostra after the 80s internal wars, to grow into a true global criminal organisation, resembling a ‘Mafia ltd’ corporate structure, to be eventually listed on the world’s stock exchanges.

The Vito Roberto Palazzolo’s Cosa Nostra is multilingual, white-collar, educated and fancy. It is rich and stylish. Bribery is done softly: politicians, officials, partners are bought, not coerced.

But even this new Cosa Nostra does not forget the old ways. And when needed, it deals in violence, street-thugs and guns with real bullets.

With Palazzolo, Cosa Nostra did not need to create a “cell” to infiltrate one society, it could virtually exist at the same time around the world, as it moves via bank cables and financial transactions. Money is laundered, cleaned, reinvested and dirtied again, in a circle without end. And Palazzolo, the key holder, sits in the middle, respected and loved. The Cosa Nostra is now intertwined with international finance, in joint-partnerships and business ventures, permeating entire governments.

Who is Vito Roberto Palazzolo?

The thing that strikes when meeting Vito Palazzolo - or Robert von Palace-Kolbatshenko, as he prefers to be known - is his green-grey eyes, set in a wide face that betrays his Sicilian ancestry, and a surprisingly deep voice for someone of medium build.

Over-all, he has the sophisticated urbanity of an international investment banker: white, light-weight cotton pants and linen shirts, perfect (his favourite word) for the hot African summer. Roberto likes beautiful women and whisky, and has a nose for the right deals and a taste for life.

Roberto loves Mercedes cars and, as a true Sicilian, could not live too far from the sea. His penthouses in the Waterfront of Cape Town, the stunning San Michele blocks on Clifton Bay, or the beach of Swakopmund in Namibia can only remind him of the beautiful Italiana homeland. He keeps the diet: seafood and salads.

He is constantly busy, taking calls on his cellphones about business deals from the Congo to Cape Town, often in many languages. He is fluent in Italian, German, English, Portuguese and French.

He is the perfect host: listening attentively to questions, answering with a short laugh accusations that he is one of the most important men in the Cosa Nostra: If he were, why would he still be working every day of his life at well over age 60?

One of Palazzolo’s apartments on the Cape Town waterfront.

The Pizza Connection

For the Italian Court that convicted him, Palazzolo is without doubt a mafia mobster, and high in the hierarchy.

According to investigators, he underwent the “Punciuta” the ritual of affiliation to Cosa Nostra at the end of the 70s. They punctured the skin of his trigger finger, smeared the blood on a sacred image then burned it while the oath was taken. This made him a “Man of Honour”, one ready to be sent to Germany, where other Cosa Nostra members were already active in the banking and precious gem trade. He worked for German companies active both in gold and diamonds, ‘Zoltan Zucker’, in Pforzheim, and ‘Cristel Biersack import export’, in Constanta. By 1981 Palazzolo had learned enough about banking cash and goods, the mafia bosses in Sicily thought, and they appointed him as head of a team of Swiss bankers who had the task of laundering the profits of a $1.6 billion heroin trade between Turkey and the USA.

In those years, most of the world’s heroin came from Turkey. Small farming communities in central regions harvested the poppy milk, and local dealers converted it morphine base. It was then transported through the Balkans, Italy, Sicily and France to laboratories which refined it into heroin and was smuggled to the United States. It was a lucrative and dangerous drug.

The Italian Mafia moved four tons of heroin each year, shipping it through the port of Newark, in New Jersey.

The trial that followed was the longest in the US history. It lasted from 1985 to 1987, and ended with 21 convictions on 22 defendants.

It was the first trial to show the massive global reach of Italian mafias. Swiss police focused on part of these transactions, and proved at least $47 million of the drug money were laundered via Switzerland: Palazzolo coordinated the creation of fiduciaries in the USA that could move the money back to Switzerland, after the cash flow became too high to be moved via suitcases and couriers. These trusts would then invest the money, mostly in real estate projects in New York, Miami, Puetro Rico and Montecarlo.

By 1984 the USA, Italy and Switzerland had figured out what was going on, and Palazzolo became a wanted man from all sides.

The Swiss arrested him under an Italian warrant, but did not hand him over. The Americans proposed immunity in exchange for turning state’s witness. But the Swiss kept him in Lugano and on 26 September 1985 a court sentenced him to three years of jail for violating the narcotics laws by money laundering.

Palazzolo managed to escape, only to rise again, like a phoenix. And this time it was for greater things.

Details in about the Pizza Connection

The Construction of a South African Empire

On Christmas 1986, using a 36 hours prison pass, Palazzolo’s escaped to South Africa. The country had already provided sanctuary to other Cosa Nostra mobsters, who became Palazzolo’s initial base. Read the details in An Italian base in South Africa.

But Palazzolo didn’t need any Italians to open up the doors to this country. Palazzolo was not your ordinary fugitive. His had the skills knowledge, and, most importantly, capital, stashed in offshore accounts, to kick-start his new business career.

Immediately he proved very useful to powerful South African figures, and started exchanging favours with the local elite.

Roelof Frederik “Pik” Botha is undoubtedly the best example. Botha, the long-serving Foreign Affairs Minister, was at the centre of all mineral, military and trade-related activities in the region, which directly affected the past and present “war” eras in Africa. Palazzolo picked friends well. In 1995, Botha helped Palazzolo obtain South African citizenship, despite the fugitive’s appearance on Interpol’s most-wanted list. Botha denied this.

Read the full story in Befriending the Establishment.

By then, Palazzolo had changed his name into Robert Von Palace Kolbatshenko; married for the second time, to Israeli and South African citizen Tirtza Grunfeld and bought La Terra De Luc, a large farm in Franshhoek where all the family lived.

La Terra de Luc is a 119 hectare estate, an area comparable to 150 football fields, with plum and pear trees, guest cottages, and all the leisure distractions one can wish for. At the centre is beautiful house: classic Cape Dutch set among tall oak trees and looking out over a rose garden and the Franschoek valley of the Western Cape.

La Terra de Luc Estate, seen from the Franschhoek hills

At Le Terra De Luc that Palazzolo could play the rich entrepreneur, inviting his influential guests to be wined and dined. Among them was his best friend Count Riccardo Agusta, an aristocrat from Italy who moved to South Africa at the same time a Palazzolo, South African politicians, like Botha, and Italian politicians such as former mayor of Milan. He also befriended a plethora of more controversial figures: corrupt police officers and local gangsters.

His life at that time was spent striking deals around Africa and buying luxurious properties in some of the most exclusive Cape Town’s corners, like Bantry Bay and the Waterfront, and large farms in both South Africa and Namibia, assets amounting to $41 million.

the ‘San Michele’ apartment block, one of Palazzolo’s properties overlooking the southern Atlantic Ocean

Yet, he never stopped being a “man of honour”, international banker for the mafia. According to the court’s guilty verdict, Palazzolo continued to manage the Cosa Nostra’s finances, providing offshore banking and money laundering services, as well as running a, yet-unidentified, diamond mine for the ruling boss of the Corleonesi clan.

The Money Laundering

Precisely because of the offshore nature of Palazzolo’s financial transactions, investigators could never reconstruct the exact amount, in millions or billions, moved by the mafia kingpin. But there was a glimpse in 1999, when South African police asked the authorities in Liechenstein

The South African police traced millions of rands sent to Liechtenstein and started to investigate Palazzolo for “money laundering”. They also discovered that Palazzolo was making great use his family Trust to funnel money towards bank accounts located in the USA, UK and tropical tax havens; money which, after several transactions, would end up again under his control.

In 2001 the High Court of South Africa dismissed money laundering charges against him, but the evidence of the ‘routes’ Palazzolo’s money took remains. Bundles of cash made from illegal activities with the mafia in Italy and abroad, according to the Italian 2006 verdict, joined Palazzolo’s own riches on a road that from a secure bank nestled in the beautiful vineyards of Franshoek would arrive from Lichtenstein, the British Virgin Islands and Manhattan, growing size, and keep until rolling back to the pockets of a the Von Palace Kolbatshenko Family Trust, Palazzolo’s in South Africa.

The offshore game allowed Palazzolo to gain incredible financial power, and penetrate South Africa’s economy through legitimate business. Palazzolo opened a water bottling plant, La vie De Luc, from his natural spring at Franschhoek farm, which is ranked in the top six international mineral waters and still today supplies numerous African airlines, including South African Airways.

And it was not just politics or industry that he tied to his puppeteering fingers: the Cosa Nostra school had taught him well in how to penetrate the justice system of a country.

Palazzolo knew how to corrupt, how to buy people, and found the task especially easy in South Africa, where honest cops are rare.

Gripping entire governments

After the Pizza Connection Trial the Italian justice never gave up trying to catch Palazzolo, and over the years sent nine extradition orders and a few missions to South Africa.

In 1995 the Italian police opened an investigation into what they called ‘the South African chapter of Cosa Nostra”. Initially South Africa seemed collaborative. In 1996 Mandela ruled for a special unit to be created to investigate Italian mafia in the country: The Presidential Investigative Task Unit (P.I.T.U.).

Under the command of sergent Andre Lincoln, the P.I.T.U. discovered Palazzolo had penetrated even the new ANC government, switching sides and leaving old friends for enemies when most convenient. P.I.T.U. documents obtained by IRPI show how Palazzolo had on his payroll important politicians and police officers. Among those, it was discovered, there were members of the South African narcotics bureau, the South Africa’s Interpol representative in London, and the powerful head of the police unit investigating organised crime, who allegedly had his daughter and son-in-law employed at a Palazzolo’s farm in Namibia.

Lincoln, while investigating the Italian mafia, worked with maximum secrecy, undercover, creating a personal relationship with Palazzolo in hope that he might give away clues to the cracks in his own government: who could be trusted and who were corrupted by the mafia. His investigation was starting to worry many influential people, so in 1998 Lincoln was forced to step down and accused of corruption, theft and fraud by other cops.

Ten years later he was cleared of charges, but the investigation into Palazzolo and others was now undermined, and South Africa showed its intentions to protect the mobster. Read the full story in How many cops Palazzolo owned.

The same kind of interests were shared also by President Eduardo Dos Santos of Angola, where Palazzolo first gripped in the 90s. Angola’s recent history is blighted by conflict.

After gaining independence from Portuguese colonialism in 1975, it fell into a devastating civil war which lasted, on-and-off, until 2002.

In 1992 the U.S.-supported UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola) captured most of the productive diamond mining sites of Angola, selling the diamonds on the black market to fund the war. It was only after the Lusaka peace agreement of 1994 that companies started investing again. Back then, Palazzolo was among the few who had the courage to invest amidst such instability. But Palazzolo had a winning plan: establish companies and place onto their boards the crème-de-la-crème of government.

When, in 1997 agent Andre Lincoln, of the P.I.T.U. investigating Palazzolo, went undercover to Angola, he reported, “It is very difficult to derail what Palazzolo has built up there. The South African chapter of Cosa Nostra is important to the security of the State because Palazzolo has many ulterior motives and it would seem he built contacts with the security and intelligence establishment of foreign countries he operates in.”

Lincoln’s words are illuminating. Palazzolo had found a way to get Angola’s ruling class on his side, and used them to obtain five concessions for diamond mining in Lusaka North, one of the Angolan provinces with best gem stone quality diamonds. In each company operating the mines, he placed crucial members of the Angolan establishment: generals, ministers or the President Eduardo Dos Santos himself.

Offshore and Diamonds

Because Angolan diamond mines would potentially provide huge profits, Palazzolo transferred the shares into three offshore entities, located in the British Virgin Islands. The exact turnover of the Angolan mines is unknown, but the value is estimated at around $280 million. Palazzolo also used the BVI to hide the real ownership of the mines, and it is only thanks to documents that were leaked to ANCIR that his involvement comes to light.

Palazzolo kept the diamond industry and the offshore closely linked, allowing him both secrecy and tax evasion, as an unreported case form 1996 also shows. Read the full story in Diamonds in Angola.

That year, Palazzolo opened a further company in the BVI, to acquire shares in Russia’s Lemonosov mine, the largest diamond mine of Europe, with $12 billion of precious stones within. Read the full story. Money for the acquisition, $2.3 million, originated half from a Palazzolo company based in Liechtenstein, and half from the Australian giant mining company, Ashton mining, with which Palazzolo had struck up a joint-partnership.

This simple deal, never uncovered before, shows how Palazzolo, while sitting in Africa, was able to pour into one Russian venture capital from the Cosa Nostra, himself, and the ‘clean’ corporate world. All by exploiting the offshore bank secrecy.

Never forgetting the origins

Throughout his business career many regarded Palazzolo as a victim, a “banker who brokered several major investments” and was prosecuted by the Italian justice system.

Palazzolo himself stated that, “State witnesses from Sicily keep trotting out their absurd allegations, saying that I run Mafia empires in Venezuela, Brazil, Mexico, Canada, even the Far East. I have a degree of intelligence and ability, to be sure, but nothing of the kind that could run the Mafia’s finances from my home in Franschoek in South Africa.”

But evidence shows Palazzolo never lost contact with the Cosa Nostra, who regard him as a crucial partner and member. In 1996, he hosted mafia fugitives; one of them, Giovanni Bonomo, was the head of the Partinico ‘mandamento’ (the ‘administrative unit’ of Cosa Nostra’s cells), the same Palazzolo belonged to. A ‘mandamento’ is guided by one ‘capo mandamento’, a boss like Bonomo, who is like a feudal lord, representing a territory of the Cosa Nostra.

Investigators proved Bonomo first stayed at Palazzolo’s farm in South Africa before then being snuck into Namibia, crossing the Orange River’s border in Palazzolo’s Mercedes. Once there he found refuge in the Namibian bush, hidden at one of Palazzolo’s farms . There was no opulence, only heat, sand, bushes and dangerous snakes. Yet, for Bonomo these were preferable to cold metal bars facing him back in Italy.

Bonomo stayed in Namibia from 1996 until early 2002, years in which the Cosa Nostra used the coast of Namibia to as part of vast cocaine trafficking operation running from Colombia to Italy. Bonomo was later arrested in Senegal, in 2004.

Close ties to Italy

Despite the distance from his homeland home, Palazzolo maintained strategic contacts with the Italian power centres, mainly through his Sicilian-based sister Sara.

In 2003, Sara and Vito Roberto Palazzolo were trying to find ways to influence the investigation into their family and, if possible, appoint a ‘friendly’ judge and to have their name cleared.

As usual for the mafia in Italy, they checked which politician they have in their pocket. The favourite candidate was Forza Italia senator Marcello Dell’Utri, one of Berlusconi’s right hand men. According to Palazzolo, Dell’Utri was “already converted” [to mafia n.d.r.] and could be of assistance.

Through Dell’Utri, Palazzolo was granted indirect access to a group of lobbyists, politicians and industrialists – people who could influence Italy’s policies. In exchange, Palazzolo promised brokerage services and to grease the wheels for a group of Italian investors, waiting to descend on Angola.

The Thibault building in Cape Town’s financial district, where Palazzolo’s family owns offices at the high floors

A Broker to Finmeccanica

In 2009, the Italian government organised a delegation of industrialists to visit Angola and attend an elegant dinner in the ambassador’s residence in Luanda. The meeting was attended by the managers of Italy’s largest industrial group, the weapon manufacturer Finmeccanica.

Finmeccanica is a public company, with majority of shares held by the Italian Ministry of Economics, a turnover of €16 billion in 2013 and over sixty-thousand employees.

Among Finmeccanica’s main subsidiaries is Augusta Westland, a military helicopter manufacturer that builds the Westland “Lynx”, the ‘fastest helicopter in the world”, used by the armies of 13 countries, including Germany and the UK.

Agusta Westland was first created by the father of Palazzolo’s good friend, Count Riccardo Agusta. It has offices and active managers in South Africa, which is the base for Finmeccanica’s activities in Africa.

At the party in Luanda, Vito Roberto Palazzolo was the special guest, allegedly invited by the South African branch of Agusta. The mafia fugitive was at ease among Italian officials and top executives.

Sources report that Palazzolo attended with some Finmeccanica managers, who had just spent a few days at Agusta Westland’s office in Pretoria. These managers introduced Palazzolo around, including to two young executives from Finmeccanica, who knew nothing about Palazzolo’s dark side. The men reported that Palazzolo was “introduced as a great agent, who made the fortune of Agusta in Sub Saharan Africa’. What was the fortune of Augusta they were talking about?

Allegedly it was Palazzolo, in between glasses of champagne, who boasted of his role as an Agusta-fleet-seller. But what fleets was he talking about?

The largest deal Agusta struck in South Africa is a controversial one. In 1999, the South African Army purchased 4.5 billion euro of weapons and military vehicles, an arms deal that included 30 Agusta helicopters worth approximately 300 million euros.

Agusta Westland beat the competitors thanks to two local companies owned by top former Army Generals and officials, hired to lobby on its behalf during the negotiations.

The South African justice calls this corruption, and is still conducting investigations the ‘Arms Deal’. Italy joined, too, after discovering that one Agusta Westland manager had openly talked about creating a black funds account for paying bribes to “African ministers”.

Finmeccanica was asked to comment on whether Palazzolo or Riccardo Agusta had a role in the ‘Arms Deal’, and on the 2001 deal in general. The company said it “has not received any court record highlighting an involvement of the company and for it will not comment on the issue”.

While both countries investigate, Palazzolo’s boastful clams in Luanda that he was an Agusta salesman acquire new power and meaning.

At that meeting in Angola, the top managers of Italy’s biggest public arms company celebrated a mafia fugitive for his ability to broker deals in Africa, while prosecutors in Palermo and top anti-mafia police units had, for over two decades, tirelessly chased the man.

The opposing priorities of two hands of the Italian state conjures a faint whiff of the treacherous “Trattativa” pact, laid down in 1992 by deviated officials and the mafia. It is a stench few can recognise, and Palazzolo is among them. He can espy it and, like an animal seeing fire, runs before it is too late.

That explains his game with the prosecutors, after his arrest in Thailand. According to L’Espresso reporting, when asked about his role in the Finmeccanica’s African arms deals, Palazzolo fell into rampart silence. But now he wants to save himself again, another way of running from the fire.

Joined byline Giulio Rubino, Cecilia Anesi

Additional reporting by John Grobler

Icons: Em L, Edward Boatman, Nick Holroyd, Chris Robinson, Iconsmind, Karthick Nagarajan, Chris Toburn, Jens Tärning, Simon Child, Sam Smith, Adam Iscrupe, Danny Sturgress, Sagit Milshtein