Kenya's Safe Haven

Apr 16, 2015 • Lorenzo Bagnoli, Lorenzo Bodrero

“Do you honestly know anyone who has never evaded taxes?” asks Mario Mele, Italian businessman and fugitive, from a table at the busy Pata Pata Cafe in Malindi, Kenya.

Mele is the cafe’s renowned manager and, from dawn to sunset, available chairs are rare in his joint. A Premier League football game plays of the cafe’s TV, but Mele ignores it. As customers flow into the Pata Pata Cafe, he manages to greet them with a quick smile, before returning to the videocamera with a worried expression.

Mele flew to Kenya in early 2012 where he started doing what he does best. He opened the Pata Pata, a welcoming cafe in the city center of Malindi, a tiny outpost for Italian tourists and businessmen on the south coast of Kenya. Malindi is a strange town for Kenya. Italian is its second language caused by the incredible numbers of expats who, since the 1970s, have moved here, looking for a fresh start or to invest in the tourism industry. Other come to just spend the winter in warmer climes, often with the company of a local, young girl.

The Pata Pata disco club (today Wip the club) in Agrustos, Italy. | IRPI

But Mele is no ordinary expat. In his native land, the Gallura region of Sardinia, which itself welcomes thousands of Italian and foreign tourists every summer, there is a trial awaiting him. He is charged with fraudulent bankruptcy for 17 millions euros.

It is a high fall from grace for this entrepreneur, a man who owned many of Sardinia’s premier night-spots, which provided expensive champagne and exclusivity to Italy’s wealthy VIPs.

“I have no intention to go back”, Mele tells IRPI reporters.

Andrea Schirra, a magistrate in the prosecutor office of Nuoro, led a year-long investigation into the bankrupcies of companies owned by Mele and his associates, Gian Pietro Porcheddu and Ivan Deidda. Mele’s companies - RISEA and EDO - went bankrupt in 2011. “We believe they were all bankrupted intentionally, in this way it was easier to make all the profits disappear,” said police officer Alberto Cambedda to La Nuova Sardegna newspaper in 2012.

A video capture of Mario Mele

Mele is now at large in Kenya. He refused to answer magistrate Schirra’s questions, but he did agree to answer IRPI’s.

“My lawyer is taking care of things at home. I can’t just go back to stand a trial and do nothing,” he says. “What will I live off while I’m there waiting, huh?”

What brings reporters to the table at Pata Pata, however, is something only partially touched on by the Fiscal Guard’s investigation.

During the fiscal check on companies owned by Mele and his business partners, police found a trace leading straight to a mafia clan from Sicily, the D’Agosta.

The Sicilian Mafia, also known as Cosa Nostra, is a criminal organization originating in Sicily, Italy. It is made up of criminal groups engaging in a wide range of illegal activities, from racketeering to drug trafficking. They share a common code of conduct and often count on local, national and even international support at a political level to evade justice.

In 1989, Salvatore Incardona was a small entrepreneur in Vittoria, a tiny city in the south-east corner of Sicily. He owned a stall in the local market, and everyone in town knew his name.

He was well-liked, but different.

The other stall-owners in the food and vegetables market paid protection money to the local mafia clan, the powerful family of Carbonaro. But Cardona refusedto pay the pizzo [extortion]. He wanted his business to run clean without filling mafia’s pockets, and invited his colleagues unite with him and do the same.

That sort of disobedience the Mafia cannot let pass. at 5:45am on the morning of June 9, a hit squad waited outside his house. As Cardona got in his car to leave for work, men unload in his directions, riddling his body and vehicle with bullets. He left behind a wife and a 25 years old son.

A few years later, the city of Vittoria and the surrounding province of Ragusa (see image) see the rise of a new mafia clan, the D’Agosta, led by Francesco D’Agosta. Francesco is the father of five children, a renown local politician with crucial connections with the underworld and local public officials. Above all he is a man with dark ambitions. He sets up his own crime syndicate and, after a period of fruitful collaboration with the clan of the Carbonaro, he decides to change sides and to challenge the powerful clan for the control of the Ragusa territory.

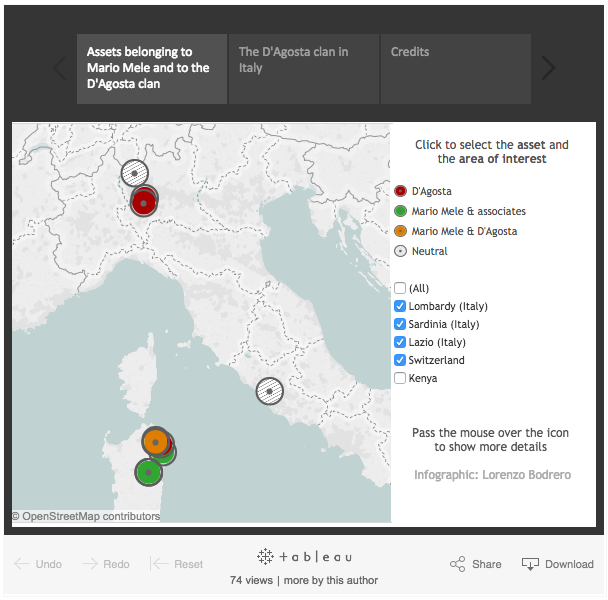

Click the image to interact with the infographic

Local media report years of killings and of bloodshed streets. The feud is on and it leaves countless bodies behind. Operation “Mammasantissima” - a slang word that mafia members use to call a boss – puts an end to the war in May 1998 when police arrest 28 people, most of which belonging to the D’Agosta clan, including the five sons of Francesco.

It is the end of the D’Agosta clan. A few months later, in September 1998, a street in the city of Vittoria is named after Salvatore Incardona, nine years after his murder.

With the operation “Mammasantissima” the names of twin brothers Gianfranco and Carmelo D’Agosta begin to appear on police reports with increasing frequency. To the extent that a few years later, Gianfranco is sentenced for the crimes of mafia association and drug trafficking. The war lost against the clan of Carbonaro must have been a good enough reason for D’Agosta’s offsprings to leave Sicily for good and to export their illegal activities in other regions of Italy.

The D’Agosta clan has always operated in Sicily and Milan, were the clan laundered money in posh pubs.

Bars and cafes were a special D’Agostas interest too. In July 2012, judge from the Milan Law Court Anna Maria Zamagni gave the go ahead for the seizure of the Samarani Cafe, a classy bar in the luxurious center of Milan, formerly owned by the mother of the two brothers. The judge believed she was a simple proxy. The same measure was also taken against the Babilonia Cafe and Il Faro di Molarotto, respectively a bar and a hotel located in Olbia, Sardinia. The entire seizure totalled € 5 million in assets. The criminal records and the individual income tax returns of the D’Agostas, believed to be too low to afford managing bars and hotels - raised sufficient suspicion for the Italian anti-mafia police to freeze their properties.

Champagne seems to be one of the links between Mele’s companies and the D’Agosta clan. Both would purchase the luxurious wine from the same company, I AM DIAMOND. Located in Rome, I AM DIAMOND sells champagne both in Italy and throughout Europe. Contacting the company’s legal representative, Simone Cavallo, for commenting has proven unsuccessful and when asked about the nature of the Rome-based enterprise, investigators shrugged their shoulders: They are fiscal police. They investigated Mele’s and D’Agosta’s companies’ revenues and that is all

During the investigation police found a copy of an € 80.000 check at D’Agosta’s house, issued to I AM DIAMOND Srl by the Lugano (Switzerland) branch of UBS bank. With thousands owed, I AM DIAMOND legal representative, Simone Cavallo, called Gianfranco D’Agosta to help him collect the credits, according to Cavallo’s testimony to investigators. By scrutinizing thousands of company documents, investigators believe that the only company entitled to issue a check to I AM DIAMOND was RISEA, therefore Mele.

“Ridiculous is the statement [by Simone Cavallo, ed.] according to which Gianfranco D'Agosta would have acted as mediator for I AM DIAMOND in order to collect the credit due by RISEA, as [D'Agosta, ed.] declared he barely knew the legal representative [of I AM DIAMOND, ed.]”.

Guardia di Finanza report, page 77

In order and to understand whether Mele and his associate Porcheddu own any assets or bank account in Switzerland, the prosecutors issued a “request for information” to Italy’s neighbouring country. The outcome is still pending.

“I have met D’Agosta once, maybe twice,” Mele says in response to journalists’ questions. “I barely knew him.” Italy’s fiscal police suggests that D’Agosta, Mele and Porcheddu might have formed a criminal association for the management of nightclubs in Sardinia. According to police records, champagne was not the only reason why these questionable parties came together.

Besides the recovery of the € 80.000 check found at Gianfranco D’Agosta’s house, police say the two had a common interest in a club called Le Burlesque, where strippers and cross-dressers regularly take the stage to entertain patrons. According to prosecutors, the directors of the club’s management company were previously employed by RISEA Srl and Il FARO DI MOLAROTTO, owned by Mele and D’Agosta, respectively.

And there is more. A 2012 police report claims that Mele purchased audio and video equipment through RISEA for installation at Le Burlesque. “It is likely that the club [Le Burlesque] is managed by Mele and D’Agosta through the use of proxy figures”, the police report states.

As admitted by the prosecutor office of Nuoro, the investigation on Mele was focused strictly on the huge tax evasion. A confidential source in the Nuoro fiscal police told us that their main interest was the dubious and fictitious movement of payments within the network of companies led by Mele and his associate Porcheddu.

Sardinia, Milan, Sicily, Kenya and Switzerland. A line connects these dots, but the details remain unclear, hidden behind financial secrecy. The “request for information” letter sent by the prosecutor office to Switzerland’s Minister of Justice may yet illuminate many dark corners. The Swiss Bank knows the real issuer and receiver behind that 80.000 € check. According to the prosecutors, it is likely that all the bankruptcies of Mele’s and Porcheddu’s companies aimed to evade creditors in a safe bank account far from the Italian Revenue.

Doubtless, the prosecutors asked the Swiss for the answers to such questions. And so the prosecutor’s office can only hope for cooperation. But the chances of success are low.

While prosecutors await an answer from Switzerland to untangle the mystery, Mele stays safe in Kenya as the trial against him and his former associates starts at the end of April 2015. His new customers seem happy and plentiful. One can only wonder if the Kenyan revenue service is receiving from Mele the full taxes that he owes from his new venture in Africa.

Joined by-line by Lorenzo Bagnoli and Lorenzo Bodrero

All texts are edited by Craig Shaw (Centre for Investigative Journalism)

This project is produced by journalism centres IRPI, ANCIR, CORRECTIV with QUATTROGATTI and made possible by IDR Grant and Journalismfund.