Africa: is Cosa Nostra

Apr 16, 2015 • Giulio Rubino, Cecilia Anesi

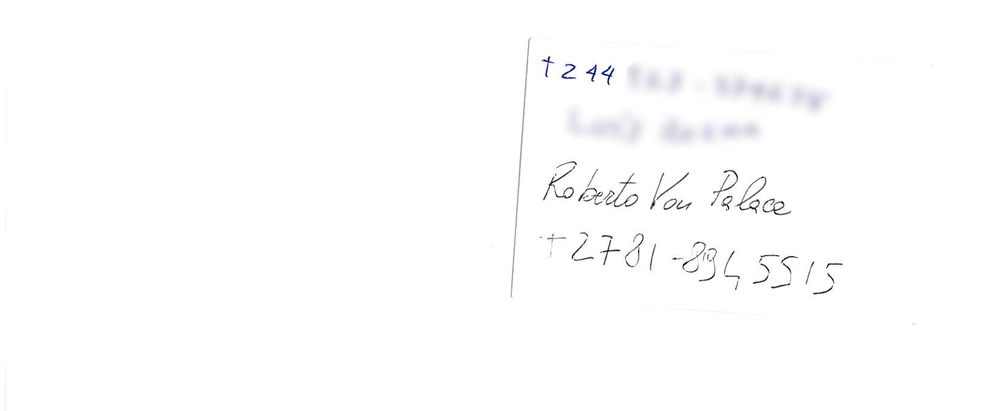

Vito Roberto Palazzolo, aka Robert Von Palace Kolbatshenko, currently sits in Milan’s Opera Prison, condemned to a nine-year sentence for ‘Mafia association’ after evading Italian justice for nearly three decades.

The former mafia banker was convicted in March 2009, after the Italian High court reinforced a 2006 verdict from a Palermo judge. South Africa, where he escaped to from Italy in 1986, refused to extradite him: Mafia association is not a crime there.

Italian authorities only managed to snatch Palazzolo in March 2012 after Interpol apprehended him passing through Thailand.

Organised crime experts regard Palazzolo as one of the most intelligent and powerful Cosa Nostra’s members of recent times - and as one of the mafia’s bankers during the ‘Pizza Connection’ era, when heroin money was laundered through US pizza joints. But few are aware of the broader picture. And even fewer know the exact features of his own vast empire.

Palazzolo is a modern Midas: all that he touches turns to gold. Between 1976 to 2012 he fostered an empire without borders. Starting in Germany, he quickly moved on to Switzerland, and then South Africa, passing unseen through the world’s tax havens.

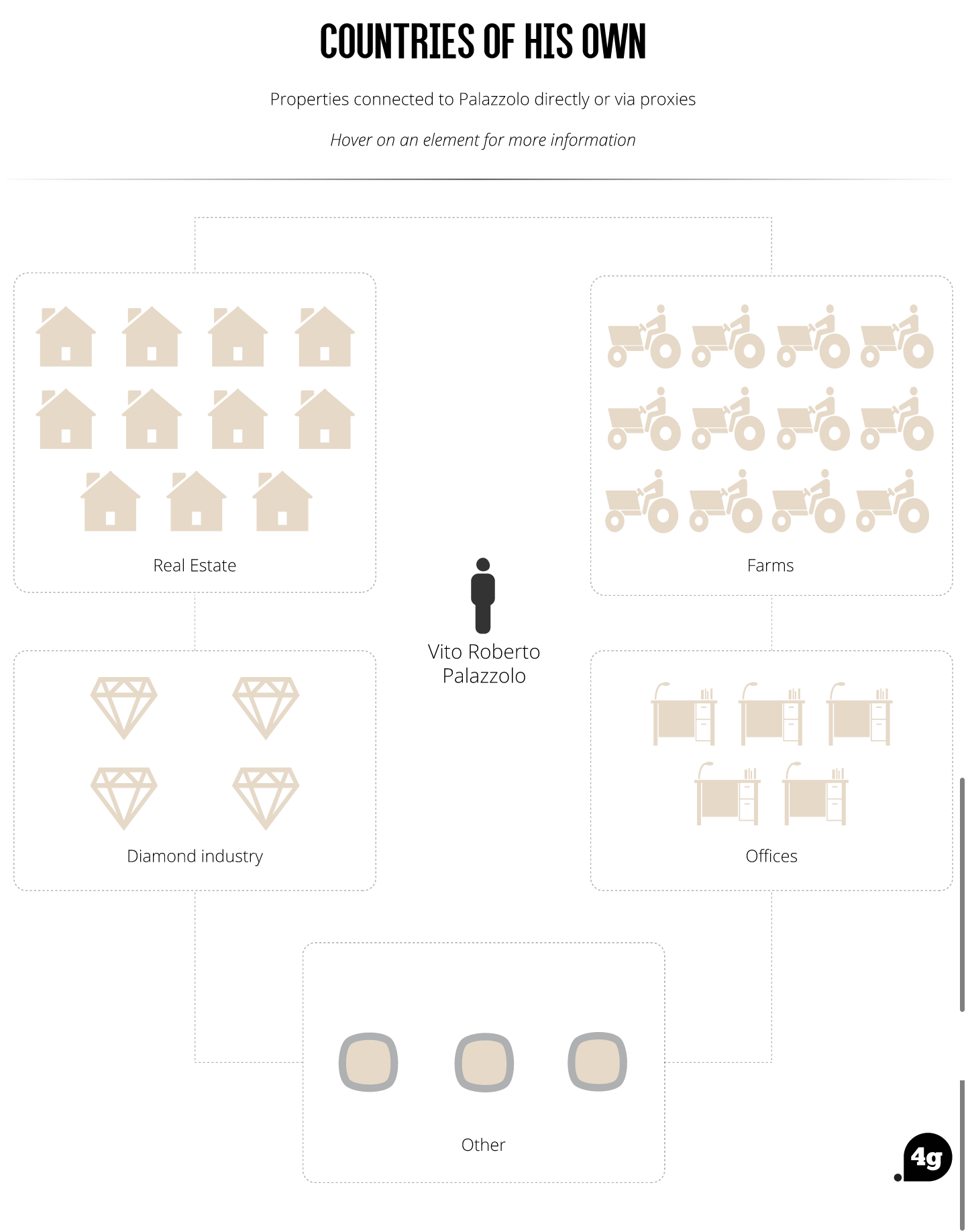

Today, from his cell, he can only dream of his marvellous African properties, the penthouse on the Victoria & Albert Waterfront, and villas in Bantry Bay in Cape Town, and the splendours provided by the profits from the diamond mines of Angola, Russia and Namibia.

Palazzolo was undoubtedly a savvy businessman and an invaluable ‘service provider’. Throughout his career Palazzolo provided the Cosa Nostra with complex money laundering schemes, profitable investments and a safe haven for fugitives; he facilitated joint diamond ventures for the corrupt oligarchy of South Africa, Angola and Namibia; and opened the gates of the Sub-Sahara for Italian industrialists.

But just how big is Palazzolo’s empire? And who manages this now that he is behind bars?

A joint investigation by non-profit investigative reporting centres, IRPI, Italy, ANCIR, South Africa and Correct!v, Germany, with the collaboration of data analysts from Quattrogatti, UK, reveals the extent of Palazzolo’s assets, deals, networks and influence.

Palazzolo’s relationship with justice is long and troubled. For years, Italian law enforcement investigated Palazzolo for mafia activities without a conviction. In 1992, a court in Rome dismissed all pending mafia-related prosecutions and charges against him. The 2006 Palermo verdict is based only on Palazzolo’s activities after 1992.

Although the pre-1992 evidence is inadmissible, the Palermo verdict claims Palazzolo was close to a number of the crime bosses of the Sicilian Cosa Nostra since the end of the 70s. Figures like Pasquale Cuntrera, Pasquale Caruana, Antonino Rotolo, the Bono brothers, Nenè Geraci and the big man, Totò Riina.

The Start: Germany and Switzerland

Born in 1947 in Terrasini, Palermo, Vito Palazzolo migrated to Aarau, Switzerland in 1962. Two years later, at the age of 17, he returned to Italy, to Rome, where he began training as a simultaneous translator. A smart young man, he picked up languages quickly and by the time he took a job on a tourist ship as “head chef” he was already mastering English, French and German.

During one cruise on the Rhine Palazzolo met a German woman, Margareta Petersen, who would become his wife. On 27 January 1966 she gave birth to his first son, Christian, with Peter following a year later.

In April 1967, at the age of twenty, he was back in Germany, in Hamburg, employed at the Deutsche Bank and making good money. In less than a year, he saved DM120,000, left his job and began working as a private banker.

By 1974, Palazzolo was in Switzerland, where he became acquainted with Myriana Konopliz the daughter of the ‘emerald king’ Konoplitz, gemmologist and owner of Konopliz S.A. Palazzolo’s brother, Pietro Efisio, was already working for Knopoliz in Antwerp as a gemmologist and diamond classifier. Konoplitz introduced Palazzolo to the precious stones trade, which at the time had already been infiltrated by Antonio Madonia, Cosa Nostra boss in Palermo.

It is not clear when exactly Palazzolo was made a “man of honour” under the mafia “mandamento” (a commission ruling on at least three contiguous mafia families) of Partinico, but by 1974 he was a mafioso, operating in Germany and Switzerland under the supervision of Madonia

By 1975 Palazzolo was in fact working with two German companies: Zoltan Zucker, based in Pforzheim and Christel Biersack Import Export, based in Constanta.

Antonio Madonia was an agent for the company Zoltan Zucker and a director for the company Christel Biersack.

Each outfit moved diamonds and gold in great quantities until they closed down in the 90s.

Hanna Zucker, who co-owned Zoltan Zucker, told journalists, “I do not want to have anything to do with this anymore as it is such a long time ago. I can look everyone in the eyes.”

Through Myriana Konopliz, Palazzolo started Pageko A.G. in Zurich, and obtained his licence as a precious stones wholesaler. As the company increased its capital, Palazzolo opened a German branch and established property investments in the States.

The Pizza Connection Trial

The 18-month long Pizza Connection Trial of 1985 was the biggest international investigation into the operations of the Italian mafia.

In the Summer of 1981 Palazzolo came into contact with Finagest S.A., a financial consulting firm from Lugano - and, in particular, its manager Franco Della Torre. Together they opened a Treuhandgesellschafft company, similar to a trust, called Consultfin.

Palazzolo said that Consultfin was set up to provide banking services for a select clientele passed on from Credit Swiss, and for trading in precious stones in partnership with Zoltan Zucker.

But Consultfin’s premium service was money-laundering. It is unclear whether Consulfin was set up with that in mind, or simply adapted to its clients’ needs, but soon it was doing business with the Cosa Nostra.

As heroin moved east from the poppy fields of Turkey into the arms of American drug addicts, at least $1.6 billion in illicit funds flowed back to the bosses in Sicily, $40 million of which went through Consulfin and other companies set up by Della Torre and Palazzolo.

Officially, the funds came from a prominent Italian industrialist, Oliviero Tognoli. Palazzolo claims he knew nothing of any illegal activities or Tognoli’s role as a mafia money launderer, stating on his website, vrpalazzolo.com, in 2011:

“In 1982, I was informed that the United States Federal Treasury was investigating the origins of Tognoli’s funds, in the USA”, he wrote. “I immediately requested Della Torre to summon his client and his associates to ascertain the source of the funds. Tognoli assured us that the funds were completely clean and legal. So I decided to complete a still-pending transaction but to terminate the relationship with this group of clients.”

With the arrests of dozens of underworld operators in 1984, Palazzolo soon became a wanted man, sought by police forces in the U.S., Italy and Switzerland.

The charge was “mafia-type association” and “having directly or as an intermediary financed the illegal trafficking of narcotics”. The Swiss authorities arrested him that same year. The Americans proposed immunity in exchange for turning state’s witness. In June 1985, Palermo’s Judge Giovanni Falcone, who was brutally murdered by the mafia in 1992, issued a warrant for Palazzolo’s arrest, but the banker was not handed over to the Italians.

Instead, on 26 September 1985 a Swiss court sentenced him to three years in jail for violating narcotics laws by money laundering.

Palazzolo’s defence is that he was not required by Swiss law to investigate the nature of the funds, saying “the edifice of Swiss banking was built on discretion and secrecy” and that the funds where linked to the narcotics trafficking in the US “unbeknown to me”.

On 24 December 1986, using a 36 hours Christmas pass, Palazzolo’s escaped to South Africa.

As a banker in Germany and Switzerland he conducted much business with South Africans looking to sidestep international sanctions by using the underworld to move money. For much of Palazzolo’s life on the run, South Africa was a haven.

An Italian base in South Africa

By the time Palazzolo arrived in South Africa in the winter of 1986, the country had already provided refuge to two important figures in his life: his brother, Pietro Efisio, and the Sicilian coffee manufacturer, Salvatore Morettino, head of Eurafrica Imports and Exports (Pty) Ltd.

In 1995, the Servizio Centrale Operativo (S.C.O) of the Italian Police grew concerned that the Morettino group was involved in money laundering.

South African Police shared this concern, believing that 8 million rand per month was being funnelled through the companies, by receiving foreign exchange from Italy, the USA, Germany, Switzerland, the UK and Mozambique, country where he had “suspicious” timber operations. The South African police discovered in 1989 that Morettino’s Eurafrica Imports and Exports had received R 650.000 from one of the banks of Pizza Connection, the Union Bank of Switzerland.

According to joint Italian and South African police investigations, in 1996 Morettino was responsible for hiding the mafia fugitive Mariano Tullio Troia, a brutal assassin for the Cosa Nostra. Attempts to arrest Troia in South Africa failed, due corruption in the local police force. Troia left South Africa unmolested, and was eventually arrested in Palermo two years later.

Morettino was never convicted on mafia allegations. Prosecutors in Palermo dismissed the charges against him. He could not be reached for comment.

The Italian S.C.O also believed there was a handful of Italians involved in the Cosa Nostra chapter of Cape Town, headed by Palazzolo.

Palazzolo was involved in some of the top nightclubs in Cape Town, including the Hemingway Club, and another company called A Table at Colin’s, established in 1994.

The latter connects an array of individuals, including Palazzolo’s two sons and Serbian criminal Goran Bojovic, wanted by Interpol for a “series of murders in the mid 90s,” five of which were conducted from Cape Town - where authorities believe he is still hiding.

Palazzolo’s sons, and the Kolbatschenko family in general, could not be reached for comment.

Befriending The Establishment

The Italian connection to Palazzolo in South Africa was just a base to start from, surely not the lever to his growth. This role that was covered by some crucial South African figures. Palazzolo wasn’t just a fugitive. He knew the secrets to banking, using the offshore, and trading precious stones. He knew how to play the queen on the chessboard, while slowing growing into a king, and at the same fostering larger reigns, those of South African friends.

Palazzolo’s first sanctuary was Ciskei, a small independent state in the Eastern Cape, later annexed by South Africa in 1994. Palazzolo arrived when the country was still in the grip of Apartheid, and quickly befriended members the white ruling class and the reigning National Party.

According to the Italian verdict, Peet De Pontes, a National Party MP, assisted Palazzolo in obtaining a residence permit. De Pontes also introduced Palazzolo to the long-serving Foreign Affairs Minister, Roelof Frederik “Pik” Botha. With Botha it was an immediate meeting of minds.

In 1995, Botha allegedly helped Palazzolo obtain South African citizenship, despite the fugitive’s appearance on Interpol’s most-wanted list. Botha would later deny this.

By 1995, Palazzolo was going by the name Robert Von Palace Kolbatschenko. He married his second wife, Israeli/South African citizen, Tirtza Grunfeld, daughter of Eugene Grunfeld, an important diamond dealer with reported links to the Mossad. The Palace Kolbatschenko family moved to La Terra De Luc, a large farm in Franschhoek. The farm was the perfect place to play host to the likes of Botha and other members of South Africa’s establishment.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Pik Botha was at the epicentre of all mineral, military and trade-related activities in the region, which directly affected the past and present “war” eras in Africa. During Botha’s tenure as Foreign Minister, the SA Defence Force (SADF) was a veritable “diamond mining company” conducting covert military and mineral deals. According to a top intelligence source, in the 1980s, Botha allegedly connected Palazzolo to SADF military intelligence operatives. This could not be corroborated by a second source.

The SADF allegedly approached Palazzolo to set up a casino for money laundering and sanctions busting in Namibia, using a nominee lawyer called Anton Lubowski. But as the venture came into effect, Palazzolo was captured by police acting under a Swiss arrest warrant and sent back to Switzerland to finish his jail sentence.

At the request of Palazzolo’s attorney Cyril Prisman, Lubowski visited Palazzolo in jail in Lugano during the summer of 1989. Back in South Africa, Lubowski expressed his discomfort over the nature of the meeting, telling his trusted secretary that he was not prepared “to do all that these people wanted from him”. One month later Lubowski was murdered by the South African Civil Co-operation Bureau (CCB), a secret Military Intelligence death squad eventually exposed by the Inquest Court under (ret) Judge Harold Levy in 1993.

Palazzolo would also be connected to a diamond company, Trans Hex later to be chaired by Tokyo Sexwale, one of South Africa’s leading black businessmen.

Sexwale was a known political activist and anti-Apartheid campaigner. In 1998, he entered the diamond trade.

Trans Hex, a leading diamond player competing with mega entities such as De Beers, would come to hold valuable concessions along the west coast of South Africa, where the most valuable marine diamond mines on the African continent are located.

In 2001 Trans Hex obtained prospecting rights in mining concessions owned by Palazzolo in Angola.

The Buying of Assets

When Palazzolo was sentenced by the Swiss Court back in 1985, he cried poverty, claiming he was so broke he could not even support his family. Italian court documents show that Palazzolo began purchasing assets and property in 1987, immediately after his arrival in the country. And when the South African police raided Franschhoekshhoek, they found thousands of dollars in diamonds and weapons.

Property deeds obtained by IRPI show that Palazzolo purchased his farm in the Cape Winelands district in 1983, confirming his connection to South Africa during the “Pizza Connection” times.

According to the state-witness Leoluca Bagarella, Palazzolo likely managed an important Cosa Nostra asset in South Africa for capo dei capi, (head of the mafia) Bernardo Provenzano: an as-yet-unidentified diamond mine.

A bottle from Palazzolo’s water bottling plant

By the early 90s Palazzolo owned farms in Plettenberg Bay and Franschhoek, as well as a luxury home in Bantry Bay, Cape Town. But the real scope of his ownership goes beyond what is in his own name. Between 1993 and 2006 his extended family, sons Christian and Peter, brother Pietro Efisio, wife Tirtza and father-in-law Eugene, acquired numerous properties in the most stunning locations of Cape Town, like Bantry Bay, Shortmarket and the Waterfront - now a stone’s throw from the Cape Town Stadium, built to host the 2010 World Cup. Palazzolo also set up a water bottling plant at his Franschhoek farm - La Vie de Luc - that supplies numerous African airlines, including South African Airways. In Namibia Palazzolo acquired numerous farms in different parts of the country, accounting for a total of 34.000 hectares and over N$24 million (about US$ 2 million). From 2006 he decided to move to Windhoek, the capital of Namibia, scared South Africa might decide and extradite him. There, he acquired a villa in the exclusive neighborhood of Klein Windhoek where he lived until the day of his arrest.

A calculus of all the properties that could be traced by IRPI/ANCIR as having passed through Palazzolo’s hands in South Africa and Namibia shows that he has owned and mainly still owns via nominees or family members $41 million worth of properties.

How many cops Palazzolo owned?

In 1995 and 1996, joint Italian and South African forces were pursuing mafia fugitive Mariano Tullio Troia. In June of ‘96, South African police raided Palazzolo’s La Terra de Luc farm hoping to find Troia. He was not there, but police did find traces that two other mafia fugitives, Giovanni Bonomo and Giuseppe Gelardi, had been there.

Mandela, then South African president for two years, requested a special unit to investigate the extent of Italian mafia presence in the country. The Presidential Investigative Task Unit (P.I.T.U.) was created, and Mandela appointed police agent Andre Lincoln to its head.

Evidence of Palazzolo relationship with policemen in South Africa shows the extent of his buying power and influence. When the P.I.T.U. started investigating Palazzolo’s networks, agents discovered he allegedly had on, or connected to, his payroll a number of current and ex-cops, including powerful general, Neels Venter, head of the police unit investigating organised crime - and whose daughter and son-in- law were employed at a Palazzolo’s farm in Namibia. Another unresolved matter is Palazzolo’s relationship with the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI): Although Palazzolo was on their most wanted list, they allegedly used him as an inside informer in Angola.

There are also unresolved questions over Lincoln himself. “Operation Intrigue” tasked the cop with penetrating Palazzolo’s networks. Lincoln went undercover, befriending the banker and following him to Angola. While there, he discovered that Palazzolo owned several diamond concessions, operated and run in close association, allegedly, with Eduardo Dos Santos, President of Angola.

When Lincoln returned from this trip, trouble started. He filed a report to the then Deputy President, Thabo Mbeki, warning that he was encountering significant opposition to his work from the South African police. Shortly after, he was arrested for corruption, theft and fraud. The allegations seemed bogus, and largely based on accusations made by Leonard Knipe, Western Cape’s violent crimes chief. Knipe had collected a statement by Palazzolo claiming Lincoln failed to repay the cost of the trip to Angola. Palazzolo also claimed he used his contacts to introduce Lincoln to the inner circles of the Dos Santos clan, rulers of the country. Knipe admitted on the record that he held animosity towards Lincoln and that he was largely responsible for his arrest. Lincoln was later cleared of any impropriety and re-admitted to the police.

In 2009, the appeal judgement clearing Lincoln established that though evidence against him ran to more than 5000 pages, the entire trial “consisted of intrigue, name dropping and very little else…”.

The judgement included the names of several high-ranking officers alongside political figures, such as President Mandela and President Mbeki. Until that time, Lincoln, a former bodyguard to Mandela, had been tipped as the next Chief of Police. In 2002, it was discovered Knipe was providing private security to Palazzo’s Franschhoek Farm.

Knipe, Lincoln and Venter could not be reached for comment.

The Genius of the Offshore

“My role at Consultfin” - wrote Palazzolo on his website vrpalazzolo.com - “where I was the CEO, and the fact that I was born in Sicily, made me the perfect scapegoat. State witnesses from Sicily keep trotting out their absurd allegations, saying that I run Mafia empires in Venezuela, Brazil, Mexico, Canada, even the Far East. I have a degree of intelligence and ability, to be sure, but nothing of the kind that could run the Mafia’s finances from my home in Franschhoek in South Africa.”

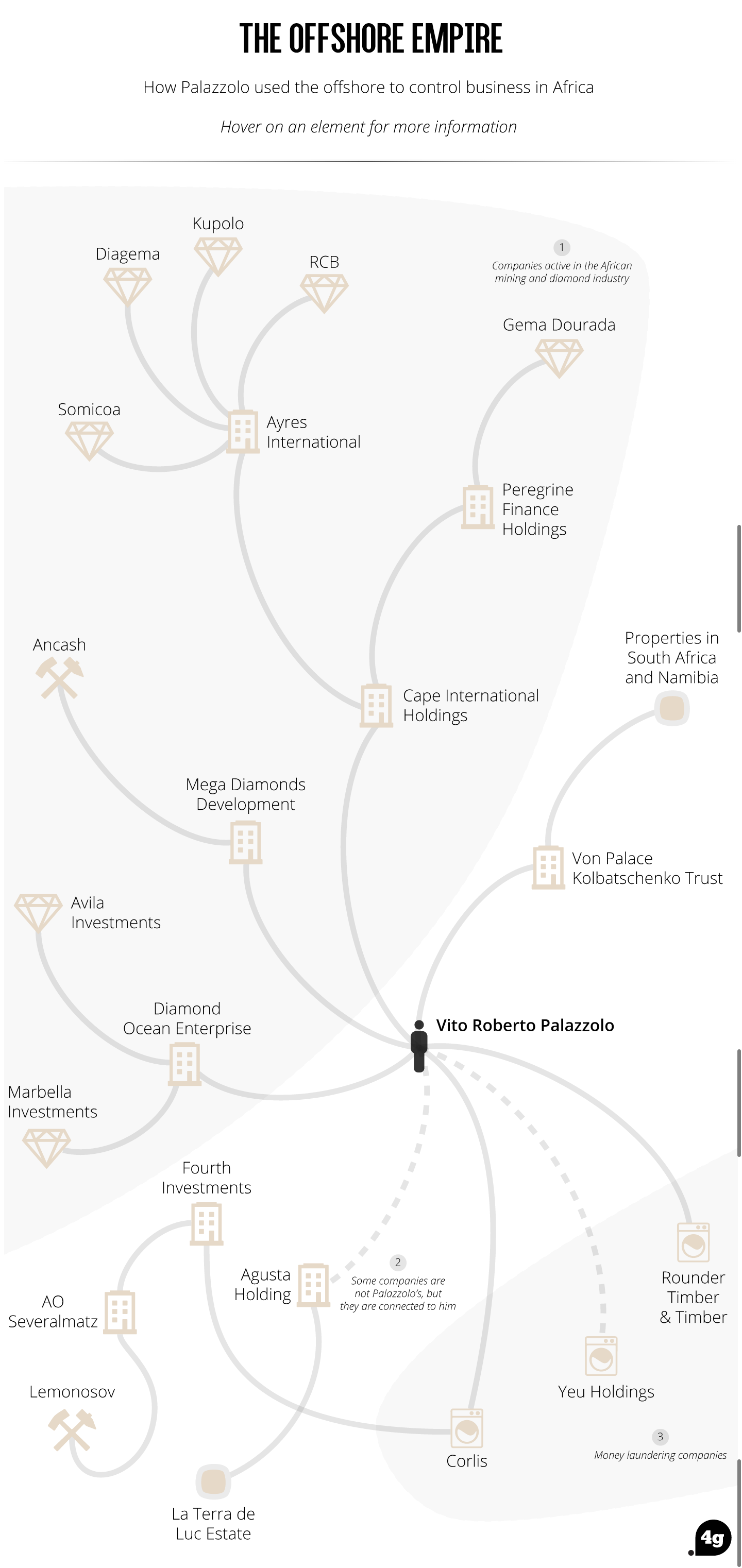

Maybe not from Franschhoek. But Palazzolo made great use of the offshore financial world to run his entrepreneurial activities. In Cape Town, he opened the Von Palace Kolbatschenko Trust, listing members of his family, including his father-in-law, as its trustees.

In 1999, the South African police requested assistance from Liechtenstein. According to preliminary investigations, Palazzolo was using the country’s financial system to launder cash in connection with a “criminal organization and illegal acts in narcotics law”, since 1986.

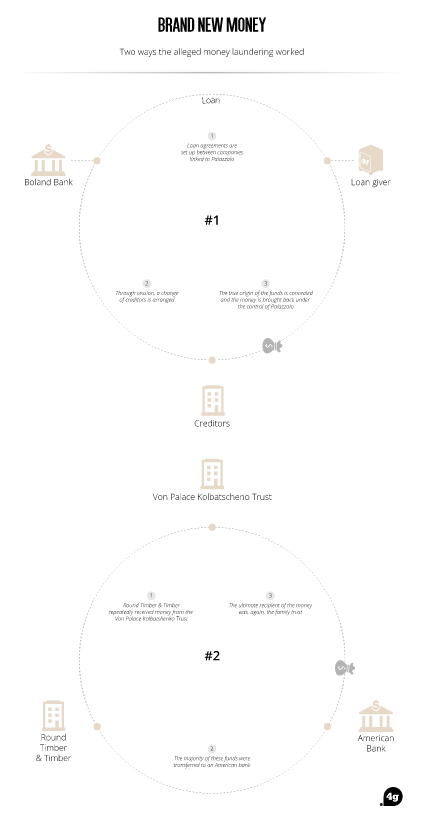

Palazzolo would, allegedly, set up phoney loan agreements using companies managed by nominees, such as staunch ally Swiss lawyer Mario Molo, or using his family trust, the Von Palace Kolbatschenko Trust.

Through cession, a change of creditors would be arranged and, via a shrewd scheme to conceal the true origin of the funds, the money circled back to the control of Palazzolo. Liechtenstein’s authorities believed a loan emitted by Vaduz based company, Corlis AG, and South African company, Spanta Development, to be a suspicious case, which shows how millions in US dollars and South African rands entered Liechtenstein via the Boland Bank, a bank close to Palazzolo’s luxury farm in Franschhoek.

Another method used the Liechtenstein company called Round Timber & Timber Products Establishment, to move money from the Von Palace Kolbatschenko Trust to Round Timber, via a US-American bank and back into Trust itself.

On 7 September 2001 the High Court of South Africa ruled that the National Director of Public Prosecutions should cease its prosecution of Palazzolo, including on money laundering charges, and was barred from prosecuting him again on the same facts. It also ruled that the Public Prosecutor withdraw all requests for mutual legal assistance to Lichtenstein and Switzerland and to return all bank statements and documents obtained during the course of its investigation.

“In line with the High Court decision, I objects the companies mentioned by you [n.d.r. Corlis and Round Timber] have been used for illicit aims”, IRPI’s Swiss attorney, Mario Molo, said. Molo is the same attorney who defended Palazzolo’s during the Swiss 1989 ‘Pizza connection’ trial.

However, the 2006 Palermo conviction delivers the definitive verdict on all Palazzolo’s illicit activities. This Court confident pronounced that Palazzolo never stopped laundering money for the Cosa Nostra. This was confirmed by state-witnesses, mafia “pentiti”, activities that took place after 1992. The year is important because Palazzolo in 1992 was cleared of mafia association charges by a Court of Rome, and the Palermo verdict condemns him only on mafia related crimes post 1992.

The Court of Palermo reserves very harsh words for the South Africa Justice system in relation to Palazzolo. It says “the direct experience lived by this Court in South Africa, the examination of documents it has acquired and the content, often improbable and almost outrageous, of some of the witnesses heard in that country under our rogatorial activity, contribute to outline a torpid situation of widespread conditioning and subjection, if not even collusion with the defendant. And this see as protagonist not helpless citizens but authoritative members of the local Institutions, heads of police and, even, a judge of the High Court.”

Investigations of South African police into alleged money laundering were stopped by the High Court ruling of 2001, but the Fiscal Guard of Palermo is still digging to find out where the real empire of Palazzolo lays. One certainty exists, and it is seems quite likely that Palazzolo did make extensive use of the offshore world, mostly to secretively control mining activities in Africa and beyond.

Diamonds in Angola

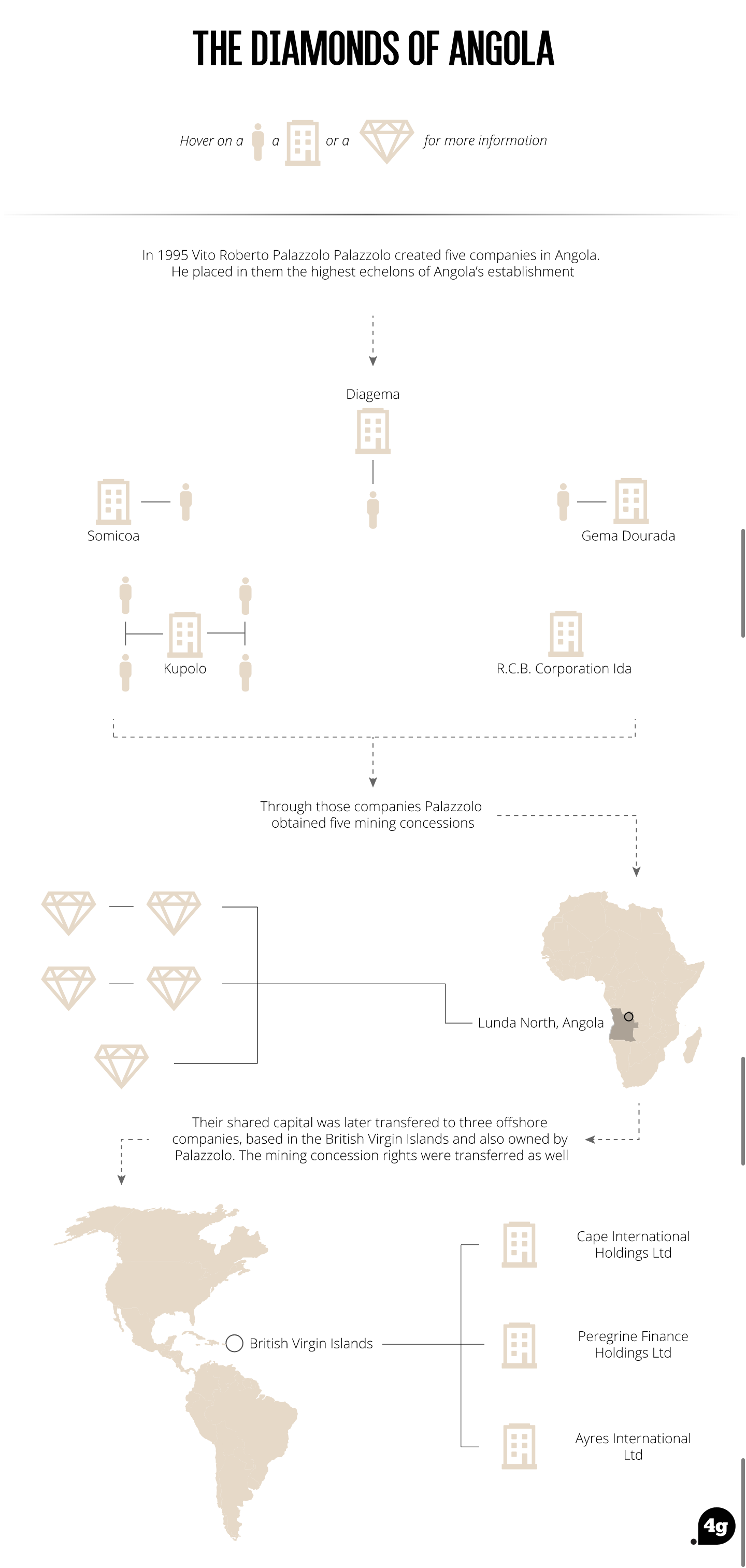

It is through the offshore world, specifically three BVI-incorporated companies, Cape International Holdings Ltd, Peregrine Finance Holdings Ltd and Ayres International Ltd that Palazzolo’s acquired six mining concession in Angola starting from 1995.

“There are a lot of companies here [South Africa] and in Angola which have been waiting a few years, mostly for something definitely less important and ambitious than ours”, Palazzolo wrote to one of his partners in the deal. “I feel that we are very close to the finalisation of some of the most important projects of Angola.”

When, in 1997 the head of ‘Operation Intrigue’, agent Andre Lincoln, went undercover to Angola, he reported that, “It is very difficult to derail what Palazzolo has built up there. The South African chapter of Cosa Nostra is important to the security of the State because Palazzolo has many ulterior motives and it would seem he built contacts with the security and intelligence establishment of foreign countries he operates in.”

Leaked documents obtained by ANCIR show more. Although it is not possible to reconstruct the first steps of Palazzolo into Angola, it is possible to assert with certainty that in 1995 he already established a solid base in Luanda, partnering up with two controversial individuals.

The first is the Italian Roberto Mattei-Santarelli, allegedly a rough diamond smuggler, arrested in Namibia in 1991 for receiving stolen goods, and again in 1994, when he was stopped by authorities in Rome airport in possession of an “unjustified” quantity of precious stones, worth about one billion lire (€500 million).

The second is Leonard Stephen Phelps, a Jewish South African banker who achieved notoriety for his unscrupulous conduct as a director of the failed Cape Investment Bank. Palazzolo cannot travel to Luanda on a regular basis. Instead he used Mattei Santarelli and Phelps as his representatives. But Palazzolo needed more than these two foreign partners to penetrate the riches contained within Angola’s mines.

Leonard Stephen Phelps passed away in 2010, Mattei Santarelli did not reply to our request for comment.

Angola is a country whose recent history is blighted by conflict. After gaining independence from Portuguese colonialism in 1975, it fell into a devastating civil war which lasted, on-and-off, until 2002. It is world’s fourth largest diamond producer by value, a legacy of few blessings. The 1980s and 90s saw two sides warring for control: on one side stood major global diamond companies, associated with the Angolan government’s most prominent individuals, and the other the ‘National Union for the Total Independence of Angola’ (UNITA), and attacked mines and sold them on the black market to pay for the war.

By 1992, UNITA had captured most of the productive mining sites in Angola, and it was only after the Lusaka peace agreement of 1994 that companies started investing again. Palazzolo was among them, and one of the few who had the courage to invest in Angola’s Lusaka North diamond industry (De Beers failed any attempt).

The mafia kingpin knew the key to success in Angola was to establish companies and bring in the creme-de-la-creme of the government. And that is what he did. In Diagema he placed General Jose Joao Mawa Mawa, the man in charge of security for the Angolan President’s. In Somicoa and Gema Dourada he placed two other key players in the State security service: General Mau Mau and General Joaquim Antonio Lopes Farrusco. When he established Kupolo, he joined with President Eduardo Dos Santos and handful of ministers, including Vice-Minister of Defense, Julio Mateus Paulo.

The bella-vita-style had to be ensured. With Kupolo, Palazzolo first opened The Tropical, a hotel & casino in Luanda, which later obtained mining concessions in Lunda North province, an area with the highest concentration of quality diamonds in the country. Many other companies followed, and each inaugurated homonymous mines.

Almost immediately, Palazzolo turned over part of the concessions’ rights to his BVI company, Ayres international. Only his Angolan company Gema Dourada was treated differently. He passed 50% of the rights to another of his BVI companies, Peregrine, which covered all mining costs.

Palazzolo then transferred the Gema Dourada shares into Cape International in the BVI, in anticipation of the arrival on the scene of a new foreign actor. On March 1996, shares in Cape International were sold to the Australian giant of oil and mining, Longreach Gold Oil Ltd, represented by Boris Ganke. The transaction was for at least US$9.8m, according to leaked documents obtained by ANCIR. South African police investigators claim that Longreach is the financer of Palazzolo’s mining in Angola, and not a simple “buyer” of concessions. According to data IRPI/ANCIR could analyse, which are partial and come from leaked documents, Gema Dourada was a deposit of approximately one million carats worth about $200 million.

In 1998 Longreach invited a new partner in the venture: Trans Hex - a company later connected to Tokyo Sexwale, who was allegedly one of the first politicians and entrepreneurs Palazzolo befriended when he arrived South Africa in 1986. Trans Hex agreed to fund 75% of the costs of exploring the uncharted blocks of mines owned by Kopolo, Somicoa and Diagema, which were worth about $80 million.

A paper on the mineral industry of Angola by George J. Coakley claims Trans Hex consultants “found and inferred resource on two of the concessions at 400,000 carats of gem quality diamond in the $200 per carat range.” In lay-speak: some of the best diamonds in the world.

Sexwale’s lawyer, Rael Gootkin, responded, “Mr. Sexwale has no personal, business or any other knowledge of a Mr Vito Palazzolo. All enquiries related to a company named Trans Hex, should be directed to that company.”

Longreach oil and Trans Hex did not reply to request for comment.

From Omburu-Sud, Namibia to Lomonosov, Russia

Undoubtedly, one of Palazzolo’s most fruitful friendships has been with Israeli diamond businessman, Gershom Ben Tovim. A resident of South Africa, Ben-Tovim inexplicably obtained in 1993 one of the most exclusive marine diamond concessions on the Namibian coast, then under licence by De Beers. How the two became acquainted is not known, but in the early summer of 1995, Palazzolo welcomed Ben Tovim into his main Namibian venture: Nacoco Ostrich Farm.

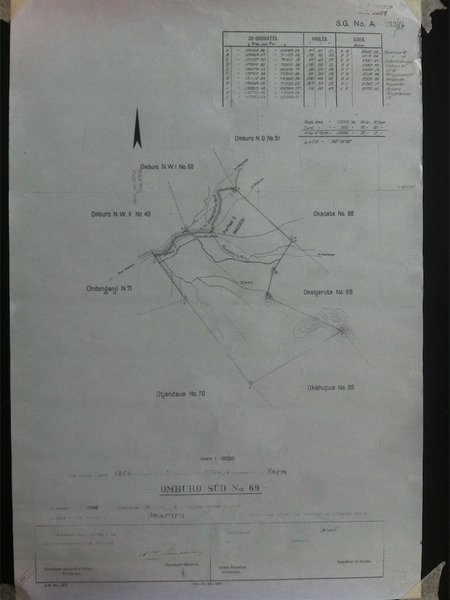

Located in the Omburu-Sud farm in the central district of Omaruru, about 200 km from Windhoek, Nacoco was an exclusive game reserve housing 10.000 ostriches, an exotic attraction for Namibia’s rich and powerful.

Perhaps it was the scorching temperatures of the Namibian bush that inspired Palazzollo and Ben-Tovim to seek deals in the cold climes of Russia. But when Ben Tovim asked for his help orchestrating the “deal of century”, Palazzolo was more than willing. The proposed venture was to obtain concessions in Russia’s Lomonosov diamond mine, the largest of Europe, situated in the north-west on the Gulf of Finland.

For this, Ben-Tovim needed a loan. Palazzolo provided it. He used his Liechtenstein-based Corlis A.G, a company that had been investigated for “money laundering” in a case that was later dismissed.

Ben-Tovim soon found another partner for the project: Australian state-owned mining giant, Asthon Mining. Palazzolo opened a BVI company, Fourth Investments Sa, especially for the occasion. Through Forth Investments, Corlis and Ashton paid for US$2.3 for 17% shares in the Russian company AO Severalmaz, which held the rights to the Lomonosov diamond mine.

At a meeting between the Australian and the Russians at Palazzolo’s luxurious Roodfontein Stud Farm in Plettenberg Bay, a South African based consortium was established. Diamonds could now be marketed to the world via Cape Town. How much money Palazzolo made from this deal is not known, but Lomonosov deposit has an estimated value of $12 billion. In 1997 De Beers was starting to show interest for the mine, and it is feasible Fourth Investment and the other Russian partners passed the concession to the giant mining company, considering in 2000 De Beers passed it to Alrosa, a Russian public company which controls Lomonosov today.

Ashton mining, a partner of Palazzolo in Fourth Investment, is now part of the Australian mining giant Rio Tinto, which did not reply to our request for comment. Gershom Ben-Tovim could not be reached.

Namibia: Home to Fugitives

In 1990, after serving his remaining sentence in Switzerland for the Pizza Connection charges, Palazzolo was free to leave the country. But in South Africa, where his family and assets were, he was now a persona non grata. So, instead, he entered Namibia on a fake Uruguayan passport and obtained residency. It was likely during this period in Namibia that Palazzolo first shook hands with a controversial man from Calabria, Italy: Saverio Polera.

From September to July 1991, with Palazzolo in Namibia, Polera was put in charge of the La Terra de Luc farm in Franschhoek, before he could head back to South Africa in 1992.

Saverio Polera is largely unknown in Italy, but his alleged diamond smuggling activities are well-documented in Zambia and Namibia. Polera, born in 1942, moved to South Africa in 1962, becoming an important figure in the diamonds trades of Zambia and Lesotho, where he is reported as very close to the Royal Family.

Polera could not be reached for comment.

According to a research by Namibian reporters, Polera is, along with Palazzolo, an associated with Sandrose’s Safari. When reporters visited the offices of the Namibia Company Registry in Windhoek to obtain copies of Sandrose’s Safari company documents the files were “missing” - stolen, according to an employee. “It happens sometimes here in Namibia,” they added.

According to the Namibian reporters, another associate of Sandrose’s Safari was Vito Bigione. Bigione previously owned a restaurant on the beach of Swakopmunt, Walvis Bay. The La Marina Resort, opened in 1999, was an old, converted oil train, and Italians who tasted his spaghetti attest that it was the best in Namibia.

But Bigione was not your normal pasta maker. He was in fact a Cosa Nostra member known as “the accountant.” And he managed cocaine trafficking from Colombia into Italy, via Swakopmunt, using the La Marina as a cover.

“Before that [Namibia]”, says Prosecutor Nico Horn, who investigated Bigione, “he was in Cameroon”. Bigione’s move to Namibia might have been facilitated by the presence of another important Cosa Nostra fugitive, Giovanni Bonomo, who fled to the country in 1996. Bonomo was capo mandamento (Commission Boss) of Partinico, the same mandamento of the Corelone mafia under which Palazzolo was associated as a “man of honour”.

Bonomo had escaped Italian justice just in time. Entering South Africa he was immediately hidden by Palazzolo at La Terra de Luc and then smuggled into Namibia, where he stayed for a while on another of Palazzolo’s farms.

Bonomo spent several years in Namibia, later moving around Africa until he was apprehended in Senegal in 2003. Exactly what he got up to in Namibia is a mystery, but his authority over Bigione suggests the possibility that he kept a close eye on the smuggling operation.

Bigione was arrested a year after Bonomo, in Caracas. During his stay in Namibia, authorities refused to hand him over to the Italians: In Namibia “mafia association” is not a crime.

Palazzolo was never asked to comment on Bigione. He did admit hosting Bonomo and Gelardi. But he maintained he did so before any charges were brought against the mafia mobsters, claiming “This is disproved both in documentation and more specifically because precautionary measures (ergo, that they were subject to criminal proceedings) were imposed on them only on 29th May, that is, subsequent to their departure from South Africa, which took place on the 21 May 1996”.

Palazzolo’s claim was rejected by the 2006’s Palermo verdict which maintained that Bonomo and Gelardi passed into Namibia before that. Again Palazzolo dodges by saying, “restrictive measures are a far cry from a confirmation of their guilt. All citizens are, after all, innocent until an irrevocable conviction is passed against them.” The Palermo verdict that condemned Palazzolo for mafia activity was also based on his contacts with Bonomo and Gelardi.

Owning Airplanes

The summer of 1999 was an important time for the Cosa Nostra in Africa. Vito Bigione was opening La Marina Resort CC in Namibia and shipping boats full of cocaine, generating huge profits and making fine spaghetti. Palazzolo’s interests was also shifting into the transport industry, having been given the go ahead for a new African airline.

Confidential documents from high level sources, obtained by ANCIR, reveals that the end of the 90s, if not before, Palazzolo was allegedly in close connection with a large mining company called Demindex. Demindex was founded in October 1996 by Pik Botha, who in that time was minister of Energy and Mineral Affairs under the ANC-led Government of National Unity. He was also allegedly a good mate of Palazzolo. Another key partner to Demindex is Rika Lourens, one of Palazzolo’s pupils. And it is precisely Ms. Lourens whom, on a fax to Von Palace Kolbatschenko date 23 June 1999, tells him that Demindex Resources Corp has been listed on the Vancouver stock exchange. She adds “the aviation licences have been granted to African Star Airways with 7 flights per week, JNB/LND and JNB/MUC”, meaning the plane will leave Johannesburg heading London and Munich. Ms.Lourens continues: “they” require US$150 million for this project, which is open to all kind of investors.

In another fax dated 20 August 1999 Ms. Lourens informs Von Palace Kolbatschenko that “prior to start up African Star Airways” they “contracted cooperative agreements” with Virgin Atlantic for the terminal maintenance in London and Lufthansa in Munich for heavy maintenance.

But African Star Airways actually never took off: its only plane, a Boeing 747-300, was bought by the African Star Airways from Singapore airlines in 1999, and after only one year it was sold to UT Finance Corporation, a subsidiary of the US based multinational conglomerate and military contractor United Technologies Corporation.

The African Star timetable advertised on their website, and handed to Airport Authorities in Munich, which foresaw daily flights from Johannesburg to Munich, would be impossible to actuate with just one aeroplane, as there are forced ‘daystops’ for air traffic from Germany to South Africa,

Both Munich’s Airport Authorities and London Gatwick Airport authorities confirm the plane never hit ground.

Ute Otterbein, spokesperson for the German Air Navigation Services, said “It is clear that African Star Airways is not known as one of the current airspace users. We are not aware of any flights by this airline from Munich to Johannesburg.”

It appears the whole African Star Airways remained a ‘paper airline’ that never started to work.

Whether this was planned for some money laundering reasons or whether it was just a failing project is hard to tell.

Joseph Kirama, former CEO of African Star Airways, on December 1999 was in trouble with the South African Revenue Service, for a 7 million rand tax evasion, while his employees allegedly were left without salary since August 1999. For an airline company that only got its license in June 1999 there was a surprising lack of financial planning.

Ms. Lourens could not be reached for comment.

Politics, Diamonds and Uranium in Namibia

Palazzolo in Namibia had interests that stretched well beyond Omburu-Sud ostrich farm.

One distinguished business partner is none other than Zacharius ‘Zacky’ Nujoma, the youngest son of Namibia’s first ever president, Sam Nujoma. Nujoma Sr was the leader of the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO) that fought against South African rule.

Zacky, 57, studied Geology in Germany and became an active player in Namibia’s rich mining sector, particularly diamonds and uranium.

Palazzolo and Nujoma have partnered up on several occasions. But Namibian sources say the association is less than equitable, and that Zacky serves as frontman to Palazzolo’s business: Palazzolo provides the cash, and Zacky, the ‘Nujoma’ name.

In Namibia, the diamond trade is regulated by Namdeb Diamond Corporation, a joint venture between the state and diamond giant, De Beers, which until 2007 managed exclusively the country’s mining sites. After 2007, a subsidiary was created to supply rough diamonds to selected sight-holders.

This change was widely criticised as a means to deter the Namibian elite from breaking De Beers monopoly over an important national resource. Presently, there are 11 authorised sight-holders - with the Namibian ruling class part of this exclusive circle.

Zacky Nujoma is among them: his company, Nu Diamond Manufacturing, is a subsidiary of Crossworks Manufacturing - one of the 11 sight-holders.

But Palazzolo’s has his hand in Nu Diamond, too. And there is a loan that proves it. On 10 October 2011, Mannheim Investments, owned by Palazzolo and his family members, provided a US$2.8 million secured loan to Nu Diamond. With this loan Nu Diamond opened its cutting works. As part to the agreement, Nu Diamond is to keep US$2.1 million worth of diamonds on its premises.

Evidence of a professional alliance between Zacky and Vito Roberto go further back. In 2005 Zacky Nujoma acquired two off-the-shelf companies, Avila Investments and Marbella investments, from Christian Gouws, Palazzolo’s favourite nominee lawyer from who he bought most of his off-the-shelves companies. As soon as Avila and Marbella obtained licenses to buy and cut diamonds in Namibia, 90% of the shared capital was transferred to an offshore company, Diamond Ocean Enterprises Limited, registered in the British Virgin Islands (BVI). Due to secrecy laws in the BVI, the true ownership of the company is unclear, but there is a significant connection to Palazzolo.

One of Avila’s directors is Von Palace Kolbatschenko Peter, registered at Apartment 7, 38 Shortmarket Street, Cape Town, the same location of Pietro Efisio, Palazzolo’s diamond cutting shop. Pietro is Peter Kolbatschenko’s uncle and Vito Palazzolo’s brother.

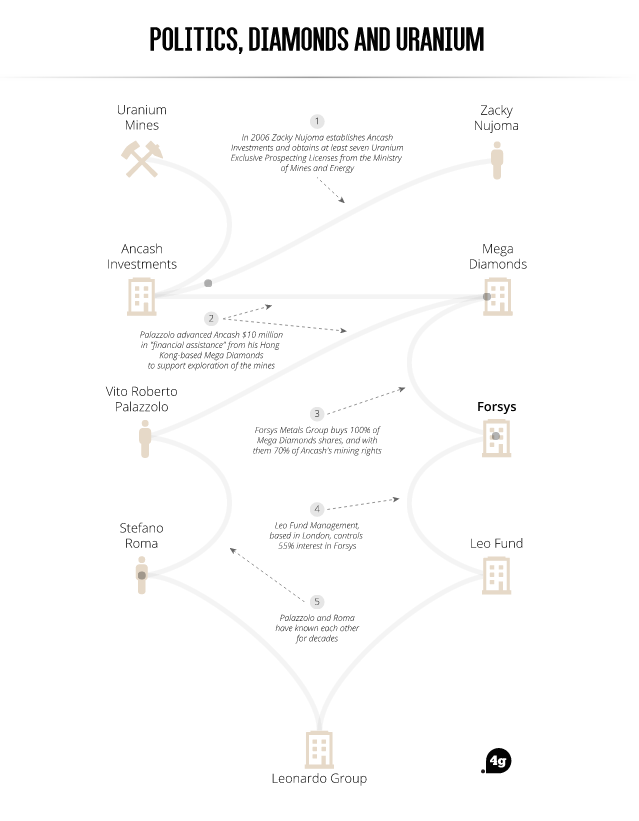

A year after purchasing Avila and Marbella companies, in 2006, Zacky established Ancash Investments (Pty) Ltd as a Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) initiative - a positive discrimination programme designed to reverse the economic inequality of Apartheid racism by putting resources into the hands of previously disenfranchised citizens.

Almost immediately Ancash obtained at least seven Uranium Exclusive Prospecting Licenses (EPL) from the Ministry of Mines and Energy. Then in September 2006, Palazzolo advanced Ancash US$10 million in “financial assistance” from his Hong Kong-based Mega Diamonds Development Ltd to support “exploration” of the mines.

Shortly after the Palazzolo loan, Canadian uranium exploration and development company, Forsys Metals Corp, announced its intention to “partner” with Ancash’s on its Uranium mining contracts. But in February 2007, instead of purchasing 70% of Ancash directly, Forsys instead bought 100% shares in Mega Diamonds, and with it 70% of Ancash’s mining rights.

It is unclear from Forsys’s financial records who is the beneficial owner at the time of the Ancash purchase, or since. In 2011, Leo Fund Management Ltd, based in London, UK, purchased 31% interest in Forsys through an $8m investment, specifically designated as working cash for the company’s numerous Namibian uranium mining operations. The main figures behind Leo Fund is an Italian businessman, Stefano Roma, and his brother, Antonio.

Leo Fund Management Ltd is part of a group of companies known as Leonardo Group, many of which are based in secretive offshore tax havens. According to its website, Leo Fund manages over €250m in investments.

The companies were set up in 2000 to serve as investment vehicles for the two Italian brothers and “associates of theirs,” according to British court documents.

According to Palazzolo, he met with Stefano Roma’s in Windhoek and Swakopmund on numerous occasions, since Roma would use Palazzolo’s speciality as an offshore banker.

Roma, who responded to questions through lawyers, claimed he was unaware of Palazzolo’s mafia reputation, and that he met him “occasionally” during one of his “brief business trips in Namibia.” Palazzolo was, he said, introduced as a “reputable and successful businessperson… very well known in the mining business in Namibia,” including to Forsys management.

A top source revealed that in 2007 Roma appeared to be leading a group of investors interesting in purchasing Forsys, including the bid by Belgian business magnate, George Arthur Forrest, whose offer in 2008 was cancelled after the US government expressed concerns over Forrest’s alleged plans to finance the take-over with cash from North Korea and Iran.

Roma denies fronting for Forrest, saying that his investment at that time was designed to „profit from the possible sale of the company, as Forsys had announced on October 14th 2008 that it was in exclusive negotiations.“

Further connections to Palazzolo in Namibia emerge through Roma’s co-ownership of a farm in Vrede, with architect Henry Mudge, nephew of a former opposition party leader Dirk Mudge, as reported by Tileni Mongudi, journalist of The Namibian.

Mudge is Palazzolo’s most trusted architect, and the man who remodelled his villa in Klein Windhoek where he lived from 2007 until the time of his arrest. The two also own a 8.000 hectares farm in Wolwedans, called Southern Cross.

Mudge admits he was introduced to Roma by Palazzolo.

In September last year, despite falling share prices, Leonardo Group increased its ownership of Forsys to over 55%.

In 2005, Stefano Roma was charged with ‘stock manipulation’ for his participation in the take-over of Banca Nazionale del Lavoro by a group of investors, including the ex-governor of the central bank of Italy, Bankitalia.

Roma was cleared in 2012: Leonardo Fund, the judge said, would have acted according to the standards of a speculative fund.

But a 2008 deal saw Leo Fund help former owners of the famous fashion company, Valentino Fashion, evade taxes on €150millon by secretly moving cash offshore.

When the Marzotto family sold some of its rights of the “Valentino” brand for €200 million, they parked the money in a Luxembourg company called International Capital Growth (ICG). The sale made the Marzotto family liable for €65 million in capital gains taxes.

Instead of paying, Marzotto decided to buy €150 million worth of shares in Leo’s Fund Cayman Island subsidiary, Leo Capital Growth Fund.

In 2013 the Marzotto pleaded guilty. Neither Stefano Roma, manager of Leo Fund, nor any other employee was investigated for facilitating tax evasion.

Forsys did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Mr. Roma told journalists that he was the beneficial owner of Leonardo Group, but claims the Forsys shares, and the uranium mining concessions, are held on behalf of two funds. He declined to reveal the backers, but said Palazzolo “is not, and never has been, an investor in any of our funds”.

He added that he had “no knowledge whatsoever of anything relating to Ancash / Mega Diamonds” in late 2008 when he first advised funds to invest in Forsys, which bought the two companies in 2007.

Roma also claims that the only assets owned by Forsys at the time were the Valencia mining concession, resulting from the purchase of Namibian Metals Ltd. Forsys’s 2007 company accounts, however, clearly show its ownership of five additional prospecting licences, acquired through the purchase of Mega Diamond and Ancash the year before for over US$13m According to a Forsys press releases at time, the Ancash mining deal “is designed to address poverty and the historical economic imbalances through the creation and distribution of wealth to the poorer communities of Namibia.”

Roma and Forsys did not reveal how many of the shareholders are poor, black Namibians.

A Broker to Finmeccanica

Over the years, Palazzolo maintained strategic contacts with the Italian power centres, mainly through his Sicilian-based sister, Sara Motisi. In 1996, Sara attempted to use connections as the sister of a kingpin to get her husband, Vito Motisi, nominated as a candidate in Forza Italia, Silvio Berlusconi’s party.

Some years later, Palazzolo asked Sara to return the favour. In 2003, Sara and Vito Roberto were trying to find ways to influence investigations, including the one which later landed him to jail.

The two brothers decided that Forza Italia party senator, Marcello Dell’Utri, was the right person for the job. In a phone-call to Sara, Palazzolo claimed Dell’Utri was “already converted” [to mafia n.d.r.], and could be of assistance.

Through Dell’Utri, Palazzolo was granted indirect access to a group of lobbyists, politicians and industrialists - people who could influence Italy’s public policies. In exchange, Palazzolo promised brokerage services and to grease the wheels for a group of Italian investors, waiting to descend on Angola. According to an intercepted phone call between intermediates, Dell’Utri hoped to “3000 Italian industrialists” to Angola.

Prosecutors in Palermo say that during this time the Berlusconi government regarded the current Italian diplomats as “incapable”, and were looking for alternative ways conduct foreign diplomacy. There are suggestions, which we could not officially verify, that government decided, unofficially, to rely on brokers to help Italian industrialists get a foothold in Angola. According to Italian prosecutors, Palazzolo, regarded as a “finance advisor” to Angola’s leadership, was a key man.

In 2004, the first delegation to Angola was organised, but prosecutors failed to reconstruct events, since Angolan authorities were uncooperative.

Then, in 2009, the government organised a further delegation of entrepreneurs to Angola, headed by the then Vice Minister to Economic Development, Adolfo Urso. The meeting was attended by Finmeccanica’s managers in Africa (Finmeccanica is the leading industrial group in the high-technology sector in Italy and one of the main global players in aerospace, defence and security) and managers from helicopter manufacturer subsidiary Agusta Westland.

Two Finmeccanica executives who attended that meeting in Angola later told prosecutors in Naples and Palermo that Vito Roberto Palazzolo was present. None of the two had any idea who Palazzolo really was, figuring out only later. Adolfo Urso, the Vice Minister, claimed that Palazzolo was there without him knowing or noticing. “During the lunch break”, recall the two Finmeccanica managers, “Palazzolo was introduced to us by another Finmeccanica’s manager, actually a manager of Selex Galileo (a security-related electronics manufacturer of the Finmeccanica group), Edoardo Fava.”

When dealing with Sub-Saharan Africa, Mr.Fava would use as a base the Agusta Westland office in Pretoria, headed by one Patrick Chabrat. It was Chabrat, Mr. Fava would have told his colleagues, who introduced Palazzolo to him as a “great agent who made the fortune of Agusta in Sub-Saharan Africa”. Mr. Fava did not respond to request for comment.

When the two Finmeccanica’s managers reported this encounter to Italian authorities they found themselves in serious trouble.

The first manager, Finmeccanica’s representative for Sub-Saharan Africa, was removed from his position. Patrick Chabrat was promoted in his place. The second manager was allegedly threatened by Chabrat, who reported to prosecutors being told he would “need a nice protection program”, according to witness statement provided to prosecutors.

But why does a company as large as Agusta need the brokerage services of someone with Palazzolo’s reputation?

Before the merging with Westland in 2000, Agusta Spa was close to the company’s founding family - and Count Riccardo Agusta in particular.

Count Agusta and Palazzolo are good friends. Since the 80s, they have managed land together in South Africa.

Riccardo Agusta began buying property in the renowned vineyards district of Franschhoek in 1990. His first purchase was La Grand Provence, adding the adjoining vineyard and winery of Haute Provence in 1997.

Palazzolo was now the Count’s neighbour, occupying the La Terra de Luc estate right next door. In 1999, Riccardo acquired shares in La Terra de Luc, and Palazzolo’s Roodfontein Stud Farm in Plettenberg Bay.

According to Paolo Piccinelli, head of the Carabinieri Unit of Palermo which caught Palazzolo in Thailand, the kingpin “sold his South African properties to the Count Agusta to avoid having them confiscated. Through Agusta Holding Co. in Hong Kong, the Count is in fact the owner of the shared capital of La Terre de Luc, Palazzolo’s luxury home in the Franschhoek valley.”

In 2000, Agusta Westland appointed Patrick Chabrat as manager head for Sub- Saharan Africa. Chabrat moved to an office in Pretoria. In 2001, Agusta signed a lucrative deal with South Africa, selling 30 helicopters to the country’s Air Force for a price of R 1.9 billion.

But the deal became part of South Africa’s biggest political scandal. Known as the “Arms Deal”, the Department of Defence was accused of receiving over one billion rands in bribes for contractors, according to British and German investigations. Agusta was named.

An agent for Agusta’s biggest competitor, U.S. company, Bell, reported how he was “asked” to hire a local company to lobby for contracts on Bell’s behalf.

The company was ‘Futuristic Business Solutions (FBS), secretly owned by General Lambert Moloi. Moloi was close to Joe Modise, the Defence Minister signing the deals, and Shabir Shaik, brother of Shamim Shaik, who headed the national defence department’s acquisitions and procurement division.

Bell refused the conditions. But Agusta had different ideas, and agreed to pay FBS, and a connected company, African Defence Systems (ADS), “large success fees” once contracts were granted to Agusta”.

Chabrat is under investigation from Prosecutors in Palermo for openly discussing how “black funds” were funnelled offshore to African ministers.

Count Riccardo Agusta, interviewed by the South African press about the ethics of the deal, stated: “I don’t think that this should be a scandal. I think that all over the world things have been, should be like that.”

Palazzolo, who allegedly made Agusta Westland’s fortune in Sub Saharan Africa, was never interviewed on whether he played a role in the arms deal.

Finmeccanica was asked to comment on whether Palazzolo or Riccardo Agusta had a role in the ‘Arms Deal’, and to comment on the 2001 deal in general. The company said it “had not received any court record highlighting an involvement of the company and thus Finmeccanica will not comment on the issue”.

Palazzolo to unveil the most obscure state secrets?

Although 2009 appears to be the pinnacle of Vito Roberto Palazzolo’s career as a broker, 2012 saw his return to mafia fugitive status. While returning from a trip to Hong Kong, Palazzolo was captured in Bangkok airport.

Finally in handcuffs, Palazzolo said he was ready to be interrogated on all “facts until 1984”. In exchange, Palazzolo wanted softer jail time. And for good reason. Italy’s organised crime figures are often subjected to harsh Article 41-bis conditions, which suspends prisoners’ rights, such as gifts and contact from outside.

In a 23rd October 2012 letter from Thailand, Palazzolo claimed that the court’s conclusions were based on inferences, and evidence “not strong enough to constitute the circumstantial threshold necessary to justify a penalty of nine years detention for mafia”. He then asked to be heard as extradited trials “in absentia are not reliable and not applied Common Law countries”.

In early conversations with prosecutors, Palazzolo was a willing witness. But when the topic turned to Finmeccanica, he stayed silent, refusing to answer questions.

One-and-a-half years under 41bis conditions changed his mind. At the end of 2014, Palazzolo decided to talk, although the content of his conversations with prosecutors is a secret.

But there is one clue as to the potential direction of the conversations. The prosecutors now interviewing Palazzolo are also assigned to the “Trattativa-stato-mafia” investigation. Trattativa-stato-mafia is the name of the alleged secret treaty between high-ranking Italian officials, deviant members of the secret services and the Cosa Nostra, orchestrated in the 1990s following the murders of judges Falcone and Borsellino.

After years of denying allegations, Palazzolo may now be cooperating. And this could have uncertain, far-reaching consequences for the Mafia and the state in Italy and South Africa, two nations that simultaneously prosecuted and protected Palazzolo.

The majority of the documents used for this story have been uploaded by IRPI-ANCIR and can be now read on sourceAFRICA.

Joint by-line Giulio Rubino, Cecilia Anesi

Additional reporting by Khadija Sharife, John Grobler, Craig Shaw (Centre for Investigative Journalism), Florian Bickmeyer

Editing by Craig Shaw (Centre for Investigative Journalism)

Infographics by Davide Mancino

Data analysis by Stefano Gurciullo

This project is produced by journalism centres IRPI, ANCIR, CORRECTIV with QUATTROQUATTI and made possible by IDR Grant and Journalismfund.

Icons: Em L, Edward Boatman, Nick Holroyd, Chris Robinson, Iconsmind, Karthick Nagarajan, Chris Toburn, Jens Tärning, Simon Child, Sam Smith, Adam Iscrupe, Danny Sturgress, Sagit Milshtein.