Charter House Bank: A Money Laundering Machine

Apr 16, 2015 • Lorenzo Bagnoli, Lorenzo Bodrero

The first alarm went off in 2001 when a request by the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) to the Charter House Bank (CHB) asking for full details about a US$20 million transaction was ignored.

The second alarm came in 2004, after an internal auditor at CHB blew the whistle over alleged malpractices.

A third and final one occurred in 2006. The shadow finance minister, Billow Kerrow, presented documents alleging blatant and widespread tax evasion by a net of companies over a period of six years.

Welcome to what it is believed to be Kenya’s largest tax evasion and money laundering scam, said to be worth about US$1.5 billion. Few are the certainties that surrounds the Charter House Bank scandal. One is that “anyone who probed the operations of CHB has been either moved off the case or has fled the country”, said one of the key-whistleblowers, Titus Mwirigi, to BBC in 2006.

One man who suffered such a fate was Peter Odhiambo, a Kenyan auditor who too blew the whistle on CHB. He was forced to request asylum in the U.S. because, according to a diplomatic cable released by Wikileaks, “the people implicated in the scandal are dangerous and appear to have bought influence in the Kenyan government.”

As internal auditor, Odhiambo had free access to the bank’s transaction documents. According to the cable sent from the American embassy, in 2004 he collected information on 85 accounts held at the bank through which, he claimed, a tax evasion scam worth US$ 573 million was perpetrated.

There is even room for some old fashioned dirty tricks. In September 2004, a fire at the CHB offices supposedly burnt to ashes a huge number of documents related to financial transactions prior to April 2004. Future audit bodies would cite the fire - as well as the unwillingness to cooperate by the bank staff - as the reason why the bank’s transfer details were not available.

The companies that Odhiambo identified as being involved in tax evasion and money laundering were associated with Nakumatt Holdings: Nakumatt Supermarkets, Tusker Mattresses, Kingsway Tyres, Creative Innovations and Village Market. A Central Bank of Kenya report went further and added the John Harun Group, Triton Petroleum, law firm Kariuki Muigua & Co. and Pepe Enterprises Ltd were also linked to the Nakumatt Holdings, stating that “they are undoubtedly involved in significant tax evasion if not other economic crimes”.

Nakumatt owns over 50 supermarket stores in Rwanda, Uganda and Tanzania and is the largest supermarket chain in Kenya. Its story began in 1978, when it was launched by Manganlal Shah. Shah is an Indian businessman who emigrated to Kenya in 1947. He started running a clothing shop near Embakasi, named Vimal Fancy Store after his first-born child, Vimal.

He moved to Nakuru town in 1952, and 20 years later he was bankrupt. In Nakuru, he started working as clerk for Nakuru Mattress, a big retail shop. His sons Vimal and Atul opened a corner shop in the same neighbourhood. In a couple of years they earned enough to buy Nakuru Mattress, changing its name to Nakumatt. The average annual turnover of the company is 45 billion KSH (€450 mln) and the company assets are valued at 11 billion KSH (€110m).

The ownership is divided into the Atul Shah family (92,3%) and Hotnet Limited (7,7%). Numerous sources report that one of the wealthiest and most influential businessman in Kenya holds part of the shares at Hotnet.

Meet John Harun Mwau, former cop and politician, entrepreneur and, last but not least, according to the U.S. Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act, one of world’s most dangerous “Drug kingpins”. “Charter House was supposed to be Mwau’s bank to launder money,” said John Githongo, Kenyan journalist and former Transparency International board member, during a phone interview. Githongo’s voice is not alone. A U.S. embassy cable released by Wikileaks details similar testimony from Peter Odhiambo, former internal auditor at Charter House. The U.S. outpost in Kenya also believed former Kenya MP William Kabogo holds shares in Hotnet.

Whistleblower Peter Odhiambo told the U.S. embassy that despite the fact that “south Asian Kenyans are listed as the owners, some of them were proxy holders of shares actually owned by the two MPs [Mwau and Kabogo].”

2006 was the turn of MP Billow Kerrow, who exposed the results of a leaked task force investigation conducted into CHB. The MP publicly linked Nakumatt Holdings and Charter House Bank to money laundering and tax evasion, alleging also that the supermarket company held a 10 percent stake in the bank.

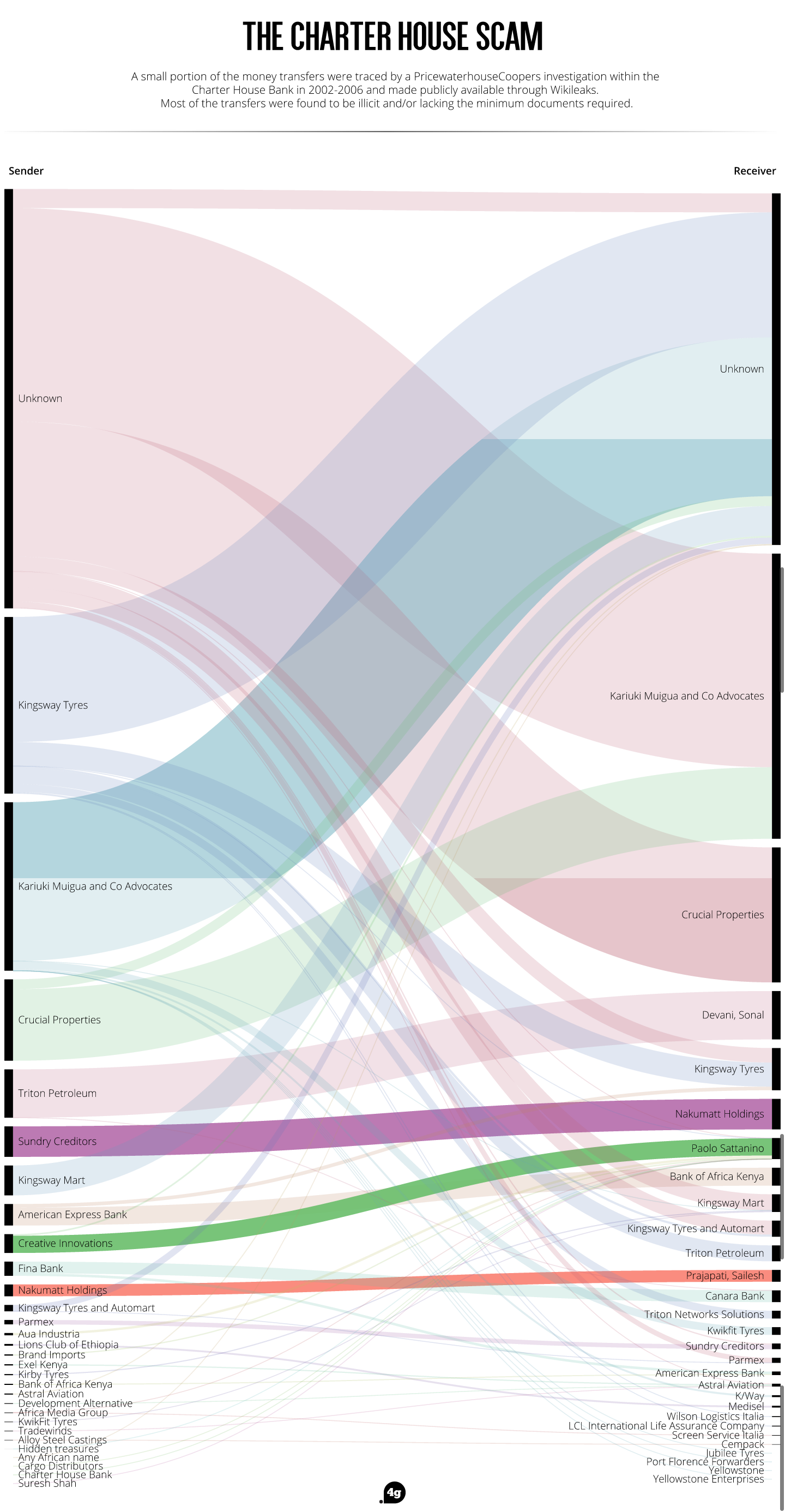

An extensive report called “Smouldering Evidence” presented by the Africa Centre for Open Governance (AfriCOG) in 2006 closely examined the CHB scandal and its irregularities. Earlier, PricewaterhouseCooper (PwC) and the Central Bank of Kenya’s due diligence team shed light on the scandal, highlighting the way money was laundered and taxes evaded. Despite the resistance they faced during inspections, they all “uncovered considerable evidence of activities suggesting that there was gross money-laundering at Charter House Bank” and that “the bank’s clients were involved in both tax evasion and money laundering,” according to the AfriCOG report. During the investigations, CHB management made it difficult for PwC and CBK auditors to operate. They “even undertook surveillance of the team’s work by mounting a CCTV camera and miniature microphone in the team’s working room.”

The report noticed how the CHB allowed money to flow to a network of companies and persons through unregistered or illicit transfers. PwC registered numerous cases of large cash transactions, both as deposits and as withdrawals. In the auditors opinion, this “indicated an intention to conceal the true source of the beneficiary of the payments made”, with each withdrawal averaging US$ 11.000. A typical modus operandi was to split a large amount of money into smaller transactions, in order not to raise suspicion within the bank’s own regulatory system: “a common practice among money launderers”, AfriCOG said. Exemplary is the case of mysterious Italian businessman, Paolo Sattanino, born in Turin in 1964.

Sattanino currently works in Lugano, Switzerland, at Mercurio Corporate SA, a joint stock company. He is the founder of Eporedia srl, Mego srl and Tradex srl, all Turin based.

By holding several accounts at CHB as a legal person and as owner of the Italian companies he owned (Capricorn Srl and Tradex Srl), Sattanino received a number of payments of the same amount within consecutive days, as shown in the image below.

Sattanino received payments from Cargo Distributors, Kingsway Mart Ltd, Creative Innovations Ltd, Brand Imports Ltd, Aua Industria Ltd. According to the AfriCOG report, he then instructed the bank to transfer the money abroad without any relevant documentation, as required for transfers above US$10.000.

Send hundreds of payments from different senders to numerous receivers, and you have laundered millions and bypassed financial regulations.

“Kindly note the above amount has been remitted to your account by Hon Kabogo” [The amount was EUR 5,270, ed.]

Email correspondence from Sanjay Shah (Managing Director of Charter House Bank, ed.) to Paolo Sattanino, July 7 2005

Journalists could not reach Sattanino for comment and the phones numbers registered to companies in which he owns shares ring endlessly. His lawyer Mauro Anetrini spoke on his behalf: “The whole story has never had any judicial consequence for my client, the Wikileaks files show that reports found wrongdoings within the bank, not from Mr Sattanino. If they asked him to provide all necessary documents he would have done so, but they never did. Besides, it is my knowledge that no investigation was done on him, why should he provide them?”. To clear his name, suggested journalists. “Ok, then, I shall ask whether he still has any”, Anetrini said.

Another peculiar Italian entrepreneur involved in the CHB scandal is Francesco Tramontano, a media businessman based in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. He is reported as having made several transfers amounting to € 80.000 to Sattanino’s bank accounts, both under his name and the Africa Media Group he controls. According to a document issued by a Belgian parliamentary committee in 2003, Tramontano was sentenced in absentia for having organised a group of people who defrauded the Belgian Development Office of €2.235.000 in aid funds. Extradition attempts sent to Tanzania have so far proved unsuccessful.

A 2012 study shows how easy it is to launder money in Kenya using shell companies. A common method was to move money across financial borders. Researchers from the University of Texas, Griffith University and Brigham Young University found that, out of 182 countries, Kenya was the least likely to ask for identification documents when people opened a shell company. With Nairobi being the financial center of the entire East African region, this makes Kenya a natural target for money launderers. The need for money laundering facilities is exacerbated by the constant political and social instability of Kenya’s neighboring countries, Somalia, Ethiopia and South Sudan.

“Another common practice in money laundering involves sending the money through a complex web of financial transactions to change its form and make it difficult to follow. Referred to as layering, it may involve myriad bank-to-bank transfers, transfers between different accounts in different names and countries to related companies, changing the money’s currency and form and so on. This is aimed at ensuring that the original illegal proceeds become difficult to trace. The PwC audit found a number of accounts that had similar patterns of transactions.

These accounts were operated by the following companies and persons: Fones Direct, Phones Direct, Intra Market Trading, Panorama Imports, Brand Imports, Triton Petroleum, Cashline Forex Bureau, Capricorn SRL, Creative Innovations, Kingsway Mart limited, Paolo Sattanino, Paul Mburu and Cargo Distributors.”

Smouldering evidence, the Charter House Bank scandal, page 8

“The proceeds of drug trafficking move through the banking system,” John Githongo tells IRPI. “In terms of movement of drug money, Kenya now rates higher even than Nigeria due to the rise of narcotics moving in and through the country, but also because of the sophisticated fiscal system that Kenya’s represents,” he adds.

Not one of the many investigations by Kenyan authorities into the Charter House scandal saw a single person in court. The bank was closed in 2006 but perpetrators are still running Kenya’s financial system, undetected or protected by secrecy.

“Normally this type of scandal would call for a transparent investigation, if the findings suggest that a criminal conduct took place then it’s the duty of the prosecution authority to call for a police investigation. The problem with countries like Kenya where the political elites have immunity is that justice is rarely made”, tells us Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime senior advisor Peter Gastrow.

In 2010, a Parliamentary committee cleared Charterhouse bank of any wrongdoing and suggested it be reopened. Instead of opening the bank, the Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission (KACC) announced that it would reopen the investigation after receiving a file from the U.S. embassy, allegedly containing details of Ksh 60 billion ($738.5 million) worth of financial malpractice by Charterhouse Bank.

Joined by-line by Lorenzo Bagnoli and Lorenzo Bodrero

Infographics by Davide Mancino and Stefano Gurciullo

All texts are edited by Craig Shaw (Centre for Investigative Journalism)

This project is produced by journalism centres IRPI, ANCIR, CORRECTIV with QUATTROGATTI and made possible by IDR Grant and Journalismfund.