Cosa Nostra Diamonds

Apr 16, 2015 • Giulio Rubino, Cecilia Anesi

Harare, Zimbabwe. Early January 2011. A man buys one million carats of blood diamonds. Cash. With rustling green American dollars, a single transaction worth tens if not hundreds of millions. He's young, good-looking and incredibly rich and powerful. His name is Antonino Messicati Vitale, and he is a boss of the Sicilian mafia, the Cosa Nostra.

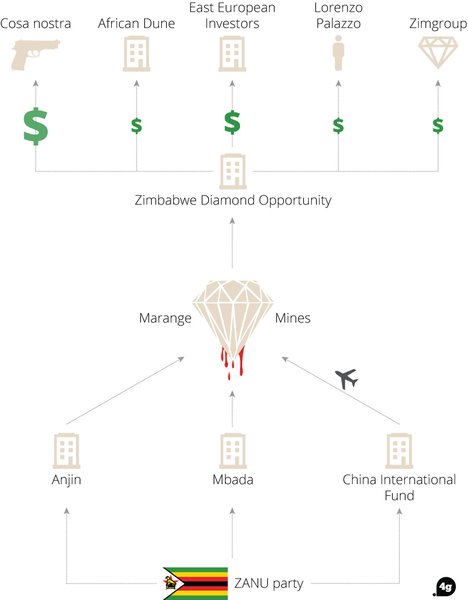

A few weeks later in Pretoria, South Africa, Antonino sits at a bargaining table with six other people. They are discussing a contract that will give rise to a new venture in the diamond trade, an agreement called the “Zimbabwe Diamond Opportunity.” The deal is between Zimgroup, a gang of Zimbabwean businessmen in charge of acquiring and cutting rough diamonds in Zimbabwe, and Ingroup, a party of international investors providing capital and marketing skills.

After the UN’s ‘Kimberley Process’ resolution was enacted in 2003, to stem the flow of conflict diamonds into legitimate markets, Zimbabwe ruled that rough diamonds could only be cut and polished locally, not exported. This rule applies not only to companies owning concessions, but also to traders. Rough diamonds, mined or bought, cannot leave Zimbabwe.

For this reason, Zimgroup has already secured the rights to open a new cutting works in Zimbabwe, and brings to the table a lucrative government contract allowing them to process 30000 carats of uncut diamonds per month. For its part, Ingroup provides not only the start-up capital, but a new Maltese company ready to market the diamonds to wealthy European customers hungry for precious stones.

But that is not all. Behind Ingroup’s sleek businessmen stands some mighty capital - the Italian mafia’s.

Well-versed in posing as legitimate businessmen, the Italian mobsters attend these meetings along with presentable front men. In Pretoria, it is Antonino’s cousin: Salvatore Ferrante jr., a South African self-made diamond trader. He is the one who will bring in investors and buyers and act as a proxy for the mafia family.

Diamonds are a perfect means for the Italian mafia’s money laundering. They don’t have a fixed value. And, if they are blood diamonds, banned ones, in the hands of the mafia they travel parallel paths and still end up on some unaware rich ladies’ neck. What has the Cosa Nostra done over the last four years to obtain diamonds from Sub Saharan Africa? An investigation by non-profit investigative journalism centres IRPI, from Italy, and ANCIR, from South Africa with the collaboration of CORRECTIV, from Germany, uncovers it for the first time.

The Sicilian Chapter

Salvatore Ferrante Jr.’s roots are in sunny Sicily, in the city of Palermo, with a fringe figure who made this deal possible. It is quite conceivable that this man cannot even find Zimbabwe on a map but he knows with certainty that somewhere in Africa his relatives are courting investors for a new diamond venture.

This man’s identity is not known to police or prosecutors, but journalists have been told that he is a prominent dentist in Palermo who spent his adult life fixing the teeth of mafia bosses.

This mystery man is the uncle of Ferrante Jr. Together they brought to their clients the diamond deal of the century.

The Mafia, however, does not entrust its ill-gotten money to just anyone; the money man must be a ‘man of honour’, a mafia associate. And Antonino’s presence in Zimbabwe with his cousin Ferrante Jr, serves as a guarantee, in Africa, that the interests of the investors brought in by the dentist will be closely overseen.

Antonino Messicati Vitale, 43, sits on the mafia throne of Villabate, a borough of Palermo and has been recently described by state-witnesses as the ‘capo mandamento’, (Commission Boss) of an even larger Palermo’s district, that of Bagheria.

In Sicily, “Messicati Vitale” is not a merely a surname: it is a symbol of great power and cruelty, and in certain parts of Palermo it is whispered with fear and respect.

Antonino’s father was Pietro Messicati Vitale, boss of the Villabate until his murder in 1988. He was shot five times on his scooter only weeks after being freed from prison. Pietro had been convicted during one of the largest mafia trials in Sicily, but a technicality saw him walk free after only three years behind bars.

His freedom was short-lived. At the time of his conviction, the mafia was at war with itself and the Italian state, and members who spent time in jail became targets for elimination: It was not worth the risk that they had been ‘compromised’ in jail - even for a boss.

In those days, Antonino, still in his teens, was already a killer, suspected of being part of the gruppo di fuoco - firing squad - of Bernardo Provenzano. Antonino is known in the mafia circles for his ruthlessness. He was described by ‘pentito’, a mafioso who turned state-witness, as “a man to whom killing is like buying cigarettes”.

When big boss Salvatore ‘Toto’ Riina was arrested by police in 1993, it was Provenzano who moved up, becoming capo dei capi, the highest boss of Cosa Nostra.

Provenzano’s ascension to Boss of Bosses heralded a new era for the mafia, shifting from the typical, violent Cosa Nostra attitude towards cleverer business thinking. “Money over bullets”, a new dogma Cosa Nostra upholds to this day.

It was during Provenzano’s reign that Vito Roberto Palazzolo, Cosa Nostra’s most valued banker and cashier, was tasked with the management of a diamond mine in South Africa, a country where he later moved to establish one of Cosa Nostra’s most flourishing foreign economies.

Antonino learned Provenzano’s lessons well. Well aware of the value of being accepted in high finance circles, ‘Tonino’ is a rising star.

In 2011 Tonino was put in charge by the ‘capo mandamento’ (Commision Boss) of Misilmeri – a territory that rules Villabate – of the economic and extortive activities in the Villabate area. Antonino had to coordinate extortion, but also the corrupt activities within the Town Hall of Misilmeri. For example the planning permission needed to turn agricultural fields into cement. Antonino was also made responsible for communication with the neighbouring ‘mandamento’ of Bagheria, of which he later allegedly became the ‘capo’, the Commission boss.

The Carabinieri of Palermo jailed him twice. In December 2012, they located him in the Indonesian island of Bali, to which he moved to escape prosecution and lived a lavish but reclusive life.

He was found and handcuffed but poor coordination between Italian and Indonesian police ultimately provided him with a reprieve: the remand term expired and police were forced to set him free. Antonino prevailed over justice, and was allowed to return unmolested to his reign in Villabate.

Back in Italy, emboldened, he continued to increase his power. But not for long. In September 2014 Antonino hatched a plan to flee Italy undetected, using a high-tech silicon mask to conceal his identity. But investigators were watching closely. And on 8 October 2014, they raided his home and arrested him. Today, Antonino is in jail awaiting trial.

“We aren’t certain about which country Antonino was going to fly to,” the head of the investigative unit of the Carabinieri police in Palermo told reporters. “But it is very likely he was going to South Africa again”.

South Africa is place where many mafia fugitives have found sanctuary over the years; it is a place where friends and family can easily shield a man from unwanted attention, while still providing a comfortable life.

The Ferrante Family

Antonino Messicati Vitale, or Tony as he is called in Africa, has a strong blood connection to the continent. His great-uncle Salvatore Ferrante Sr emigrated to South Africa at the end of 50s and immediately established a large family.

Salvatore Ferrante, relative of Antonino Messicati Vitale and diamond trader

In the 60s Salvatore married a South African woman, Wilhelmina Marais, with whom he would have six children: Salvatore Jr, Giuseppina, Alberto, Anna Maria, Carmelo and Bianca. It is clear even from their social networking profiles that the Ferrantes are a tight, Italian style family, combining a love of family with a love of the good life. Posted on their Facebook pages are scores of pictures of expensive cars, luxury homes and racehorses. The family also have a pet tiger.

Little is known about Ferrante Sr’s first steps in South Africa. Perhaps Salvatore was just a young immigrant from poverty stricken Sicily, seeking to find his fortune in new surroundings. But this seems unlikely. Sources agree that Ferrante Sr moved quickly into the gold business, notably the mines of Springs, east of Johannesburg in the Gauteng region.

By 1977, he had become a director of BDO Nominees, the South African branch of BDO International, one of the largest accountancy and consultancy networks in the world.

But whatever the early fortunes of Salvatore Sr, the family was not rich.

Investigators from the Italian Carabinieri military police unit from Palermo had no reason to investigate the Ferrante family.

But in 2011, the Carabinieri added as a Post-it note to the wall of its offices. Antonino Messicati Vitale took trip to South Africa to visit the Ferrantes. And so the head of the investigative section of the Carabinieri in Palermo, began researching the Ferrante family business. On the website of one company, African Dune, was a copy of the drafted contract for the “Zimbabwe Diamond Opportunity”, displaying a picture of the bargaining table and its seven conspirators. To the Carabinieri’s surprise, one of the faces among them belonged to Antonino Messicati Vitale.

A New Member to the Family

from the Zimbabwe diamond opportunity contract, the table of the negotiations

In the picture of the meeting, Antonino, half hides behind his uncle Salvatore.

In the centre of the photo, leading the negotiations, is a man who wears the widest smile of all: Louis Petrus Liebenberg.

Mr. Liebenberg at the time was regarded both as a crucial business partner to the Ferrante family, and a new “family member.” He was in a romantic relationship with Salvatore’s eldest daughter, Giuseppina, called Pina by friends and family.

Liebenberg is a prominent businessman in the South African diamond industry, as trader and concessions holder.

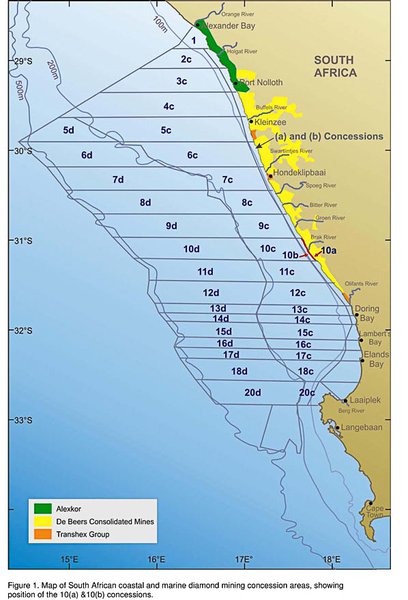

Born 1964 in Port Nolloth, 85 km away from the Namibian border, Liebenberg is the son of a Parish Pastor.

One day, a wealthy member his father’s congregation, Johannes Huisamen, decided he wanted to help the young pastor’s son. At the time, Huisamen owned the mining rights to some the most exclusive marine diamond concessions along the western coast of South Africa close to the Orange River mouth, including those of ‘Concession 10’.

Map of marine diamond mining concession on South Africa’s west coast

Perhaps he wished to carry favour with the Lord, but Johannes Huisamen passed Liebenberg the marine mining rights to ‘Concession 10’. It is one of a few privately owned marine concessions, where mined diamonds can be sold privately and do not have to pass through the South African State.

Concession 10 diamonds are among the best in the world. “They have got 99.9% gemstones quality,” explained Liebenberg. “They have been carried by the Orange River for 240 kilometres up to that point and it has been through the waves and all the impurities are gone”.

In 2005 Liebenberg opened the Wealth4u Mining and Exploration LTD to work “Concession 10, which “has at least 600 million tons of diamond gravel to work,” Liebenberg told IRPI reporters on 23 January 2015. “There are up to 2 million carats of diamonds laying there.”

Two years after opening Wealth4u, Liebenberg’s fate became intertwined with Ferrante’s.

“It was 2007 when I met Pina at a restaurant in Johannesburg,” Liebenberg said. “I did not know that [the Ferrante’s] work method was to send out the women to meet wealthy men in South Africa. Pina and a friend of hers attended several restaurants where rich men ate. There they would chatting the men up and invite them home”.

Pina is a typical Sicilian beauty, dark haired with dazzling blue eyes. She is charming and fun, and men like her.

“Pina and I started seeing each other on a regular basis,” Liebenberg said. “But she would always say she would rather stay friends, and so we kept seeing each other for about ten months - just as friends”.

Liebenberg was, at that time, going through a difficult period. Romance was not a priority: his main concern was ‘Concession 10’.

He was attempting to raise the capital needed for Wealth4u to exploit the mine. In 2008 he listed the company on the London Stock Exchange. “I raised 150 million rand on my own, without any broker, to expand operations on the West Coast of South Africa,” he said. “And then I raised another £30 million through the London Stock Exchange”.

Today the entrepreneur believes Pina preyed on him because of his wealth, and that after his successful trip to London SE, she changed her mind, deciding she then wanted to be more than friends.

“I started a relationship with Pina in February 2008.” he said. “I was still going through the divorce and it was a very expensive one. Pina said she could protect me against my wife’s claims and that I could put all my assets in her name.”

Liebenberg mulled over the proposition, and then Pina introduced him to her family, an important step for an Italian daughter, who told him how much they wanted to help.

“You know, being Afrikaans, we are not that close to family,” Liebenberg said. “I liked the fact they were very supportive of me going through my divorce. We were always having dinner and lunch together and it really felt like a family.

“I was obviously going through a tough time emotionally and personally,” he added. “I am an artist: I used to be an opera singer. I love people and I love the connections and so on, so I was an easy target.”

Liebenberg began to trust the Ferrante family, eventually accepting their offer.

Almost immediately, he employed Anna Maria as a secretary, and appointed Alberto and Carmelo managers of two important mining concessions, the West Coast’s ‘Concession 10’ and another one in Kimberley.

He also accepted Pina’s proposal, transferring all of his assets to the Ferrantes. Although he kept his role as CEO of all the diamond companies, he was now technically working for the Ferrante family.

And the deal was not limited to the companies: “They convinced me I must take all my animals, my cattle, boats, equipment, all of it, and put in Pina’s name,” he said. “And I did that”

To many, such unbridled trust of near-strangers would be out of the question. But for Liebenberg, it was a lesson he learned the hard way: “I had a ranch. I had 2000 cattle on the farm. I had racehorses, some of them very valuable, up to R2.3 million. I had some of the best horses of South Africa, and I put them all in her name”.

With the assets now Pina’s, and Liebenberg’s wife heading to the courts, the family decided to liquidate Wealth4u, transferring its assets and rights to Concession 10 into African Dune Ltd, owned outright by Pina.

Investors who poured over 100m rand into Wealth4U were concerned that the assets of a multi-million rand company, including the valuable Concession 10, were now the property of African Dune, officially bought at auction by Pina for the rock bottom price of just over 2m rand.

Liebenberg was forced to reassure investors, telling them that they would not lose money if they signed up with African Dune, free-of-charge.

But even with his legal position now shaky, especially with Concession 10 in Pina’s hands, Liebenberg remained excited at the future business possibilities. He thought he had taken all the necessary steps to protect himself. But a fool in love is no ordinary sucker.

“We wrote an agreement that was kept in the office safe,” said Liebenberg. “If you get to know Afrikaners, we are very trusting. We believe you. We still do business with a handshake. So I thought that was enough.”

Liebenberg was confident of his contacts in the mining world, which Pina and the Ferrante family needed in order to enter the diamonds trade.

The Colonisation

Diamonds ready to be cut | African Dune company website

From mid-2009 until the end of 2010, the Ferrante-Liebenberg partnership appeared to only expand. The Italian family wanted to trade diamonds with as many African countries as possible.

And so the South African trader decided it was time to open up his little black book of contacts and bring the Ferrantes properly into the business.

Liebenberg contacted two governors he knew from the Kasai-Occidental and Kasai-Oriental provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where the best diamonds in the country are located. He had been trading with the politicians since 2007, buying diamonds and exporting them to India.

He organised a meeting with a key character in Johannesburg: Marius De Kock, son of the former governor of the South African Reserve Bank, and a sight-holder for De Beers, one of the world’s leading diamond producers. Sight-holders are authorised to bulk-buy rough diamonds on behalf of De Beers. And the Ferrantes were very interested in the kind of deals they could make through him.

Marius De Kock proved to be a well-greased hinge on the door to Angola for the Ferrantes. Back in Springs, while the Ferrantes and Liebenberg made plans to grow their trade, talks took place in the sumptuous home of steel magnate, Franco D’Arrigo.

D’Arrigo is a close friend to Salvatore Ferrante Sr. “His father and Pina’s father where very good friends,” said Liebenberg. “They came to South Africa together. D’arrigo is also friends with Isabela Dos Santos, the Angolan president’s daughter”.

Liebenberg had an idea. “I sent Marius De Kock to Angola, so that the Ferrante and D’Arrigo could be linked to De Beers there”, he told us. This information could not be corroborated by a second source as D’Arrigo did not reply to a request for comment and Marius De Kock could not be reached.

But Marius De Kock was also instrumental in the push into Zimbabwe.

Liebenberg made preliminary deals with the Zimbabwean government: “I made deals for 50.000 carats a month,” said Liebenberg. “My partners there were Billy Tanhira and Doctor Baatzi who introduced me to the Director General of the mining in the Marange province.” Marange is the most important diamond mining area of Zimbabwe, and Liebenberg had just struck a hell of a deal, for the Ferrante.

But Ferrante Jr wanted his hands in the deal. “Salvatore said he wanted to go and meet [Tanhira and Baatzi] and cement the deals, and so I asked Marius De Kock to take them to Zimbabwe.”

In late 2010, De Kock travelled to Zimbabwe with a large delegation of investors from Italy and Europe, put together by Salvatore jr, who now divided his time between South Africa and Italy.

Salvatore seems accomplished at finding investors in Europe. While his uncle, the nameless dentist of Palermo, was collecting Cosa Nostra’s money, Salvatore hooked a group of shady Swiss, German and Bulgarian investors, demonstrating how a single venture could unite clean South African entrepreneurs, dubious European sponsors and the Italian mafia.

According to Liebenberg, another investor scouted by Salvatore Jr. is Lorenzo Palazzo, from Bari, Italy. Palazzo is an active mining entrepreneur in Ghana, and offered to not only pour two million dollars into the Zimbabwe Diamond Opportunity, but also collaborate with the Ferrante in Ghana’s own gem mines. Palazzo refused to answer questions from journalists.

Blood Diamonds? I Buy them cash.

Marange has the largest deposit of diamonds of Zimbabwe. After the prospecting rights expired for De Beers in 2006, President Mugabe’s ruling party, ZANU-PF, swooped in with the intention of extensively mining the valley.

To do so, ZANU first had to “liberate” Marange from thousand of poor civilians. With Zimbabwe suffering an economic crisis, civilians in their thousands flowed to the diamond fields, hoping to find a few gems.

Operation Hakudzokwi, or “You Will Not Return”, took place in late October 2008. Fifteen hundred Zimbabwean soldiers armed with automatic weapons and military choppers, trapped and then massacred hundreds of civilians.

Following the carnage, the Kimberley Process (KP), imposed a sales ban on Marange diamonds, lifted only in November 2011.

In January 2011, Antonino Messicati Vitale visited Zimbabwe with his cousin Salvatore Ferrante Jr and a group of Swiss and Bulgarian bankers. They were cementing connections for the Zimbabwe Diamond Opportunity, and scouting other deals.

Back in South Africa, Antonino was introduced to Louis Liebenberg, by Pina who referred to him as “our cousin, Tony”. “He stayed with Pina and me for a whole month,” Liebenberg said. “He wasn’t fluent in English, but could understand. He brought lots of expensive gifts from Italy to the family. I only got to know what Pina told me about him: that he was her cousin and had lots of money. I only discovered later, on the press, that he had been jailed for mafia.” It was during this month that Antonino returned to Zimbabwe, this time to Marange.

He came back with one million carats of diamonds, purchased in cash.

Marange’s diamond prices vary significantly according to a gem’s quality, colour and purity. The minimum set price is $70 per carat, though it is possible access the highest quality stones costing up to $450 per carat, “if,” said a parliamentary source, “buyers specifically request it and get it direct from mines”.

Buying one million carats with cash is unimaginable to Europeans, but is daily life in Zimbabwe. “Significant parcels of diamonds are sold to dealers,” the source explained. “[Dealers] fly in, buy the diamonds in classified parcels and after transferring the funds, fly them out. They do not go through customs or immigration [control]. The Military are deeply involved.”

So when Messicati Vitale entered Zimbabwe in January 2011, he left with between $70m to $450m worth of illegal diamonds. Where these diamonds are now is speculation, but many of them likely made it onto the fingers or necks of rich Europeans, who are unaware that their expensive purchase is tainted with blood and mafia money.

Marange Diamonds and the Zimbabwe Diamond Opportunity

But the bloodbath of Operation Hakudzokwi was not enough to shame the Mugabe government. With the blood barely dry, the Marange fields became an exploration ground for a new Sino-Zimbabwean partnership. And ZANU called in its three secret partners.

The first, Anjin, is a joint venture between China’s Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Company (AFECC) and a shell company called Matt Bronze Pvt. According to Deputy Mines Minister Gift Chimanikire, the Zimbabwean Defense Industry (ZDI) was a 40% shareholder.

The second partner, Mbada, is a partnership between Grandwell Holdings and the state-owned Zimbabwean Minerals Development Corporation (ZMDC). Grandwell Holdings is registered in the Mauritius, and hides the same beneficiaries of Anjin: Zhang Shibin and Cheng Qins.

The third company, China International Fund (CIF), is a Hong Kong-based firm closely associated with China Sonangol, whose shareholders include Angola’s state-owned oil company Sonangol. An article published by 100 Reporters, a US-based investigative platform, detailed the use of a plane owned by Angola’s Sonangol, utilized for the smuggling of great quantities of diamonds.

In 2013, the three companies were found to be sponsoring Mugabe’s 2013 electoral campaign. The support, as suggested by the Chinese Communist Party itself, included the “absolute neutralization of the enemy”, carried out – according to Zimbabwean Intelligence (CIO) documents obtained by ANCIR - using “thousands of young men” armed with “assault rifles”.

Since 2009, the three companies have extracted from the Marange fields an incredible number of diamonds. These gems were either sold to India via Dubai, or to local acquirers such as Billy Tanhira, a Ferrante man.

The contract Liebenberg obtained for the Ferrantes allows them to purchase up to 30.000 carats per month in Marange diamonds, meaning they are purchased from Anijn, Mbada or CIF.

“I sent my cousin up to Ghana to help the Ferrante with the equipment in the new ventures with Lorenzo Palazzo,” said Liebenberg. “When Palazzo came down to Zimbabwe, he and Ferrantes also wanted to start buying diamonds directly from the Chinese of ANJIN, the largest mining company of the world with rights in Marange”.

The Ferrante picked the right time to buy Marange diamonds. A Zimbabwean Parliamentary source told journalists that at its peak in 2012, “Zimbabwe produced $3,5 billion in rough diamonds”. One can only guess at exactly how many millions of carats have been moved by the family since 2011, and at the enormity of the profits gained.

Mafia Diamonds

Antonino Messicati Vitale, the mafia boss from Villabate, is not listed in the “European Group” of investors, but after his visit to South Africa it became clear the Ferrante family was relying mainly on their relative Antonino to fund the new diamond operations, Liebenberg told IRPI.

Only a few years after joining with Liebenberg, The Ferrante family were well-connected in the DRC, South Africa, Angola and Zimbabwe. There is a steady flow of cash coming in from Europe. But the money, Liebenberg discovered, was not flowing into African Dune’s bank accounts as expected. Instead, the cash was funnelled into a new company, Mpreaso Mining, set up by the Ferrantes without Liebenberg’s knowledge.

This means that the Zimbabwe Diamond Opportunity was now pretty much a dirty venture for the Cosa Nostra, whose own money originates from violence, drugs, extortion and all manner of other illegal activities.

Losing Concession 10

The Orange River Mouth, border between South Africa and Namibia, where the most precious marine diamonds concessions are

On 2 March 2011, a diver drowned during the preliminary exploration dives in the shallow waters of South Africa’s Concession 10 site, but not before finding 8.6 carats of diamonds.

Alberto Ferrante, one of Salvatore Ferrante jr’s brothers, who was in charge and responsible for the proper operation of the life support machinery for the diver, could not prevent the accident, said Liebenberg.

The investigation that followed stopped all further explorations on the concession site, and De Beers, which owned the land on the coastline where the ports and warehouses were based, locked African Dune out, effectively preventing the work from continuing.

Liebenberg fired Alberto Ferrante, but this was, in his own words, “ the biggest mistake of my life. I never thought if you fire one the whole family will turn against you.” From then on the Ferrante family’s main focus was to the get rid of Liebenberg.

“At this point it seemed the Italians were not interested in working the concession,” Liebenberg said. “They were, rather, only interested in buying and selling diamonds”. It was clear Liebenberg had been used as a gate to Zimbabwe, mainly, and that Concession10 was not their priority.

With enough time and money, the West Coast project could have been a lucrative venture. But the mafia is averse to risk. Diamonds are commodities, bought and sold quickly as way to clean money. And in this regard, Zimbabwe was far more important.

Liebenberg should have smelled something fishy, but remained trusting.

At around this time the Italian investment attracted the attentions of high-ranking South African government officials, who asked him to be included in the deal.

“I was put under lots of pressure because I could not get concessions in Zimbabwe” he told reporters for IRPI, “and then the government approached me through one of the shareholders of Whealth4u, and said I must bring in a very prominent individual, General Lambert Moloi.”

What happened next, Liebenberg does not know. The Ferrantes, he said, excluded him from the meetings.

Entering into war with the Ferrante

It was now open war between the Ferrante Family and Liebenberg, and at the beginning of 2012 Pina’s and Louis’ romance came to an end. But when Pina heard Liebenberg was seeing other women, as he claimed in his court affidavit, she convinced him she could not live apart.

On 16 May 2012 Liebenberg agreed to let her visit him at the flat they had once shared, above the offices of their cutting shop in Johannesburg. The two had sexual intercourse. But as Liebenberg showered, the police arrived. Pina accused him of rape.

“I was arrested and kept in jail for 11 days,” he said. During this time the Ferrantes took the diamonds from the office’s safe, and the written agreement on the real ownership of Liebenberg’s assets. Liebenberg was left with nothing, and at that point, he explains, “they owned me”.

According to the affidavit, the Ferrantes also changed the registration numbers of all the cars which belonged to the Liebenberg. “I had no control over my office, my papers, my videos,” he said. “I had filmed every meeting, but now I have no proof of anything, my computer is still there. And in the meantime they began selling all the assets.”

Liebenberg was found not guilty of rape. And he claims that he was physically intimidated by Pina’s new man – head of a private security firm in Pretoria. “I had to get police protection at the trial,” he said. The new man, with bodyguards from his security firm, told me ‘you’re going to be dead.’ They would come to my car and stand around it, and would not move”.

In March 2013 Liebenberg decided to drag Pina into court reclaim his assets. The legal battle is ongoing.

Liebenberg reports he still receives death threats over the phone from people connected to the Ferrante.

That family is flying

The Ferrante seem unafraid of the North Gauteng High Court of Pretoria, and Liebenberg’s lawsuit. The family ‘s business keeps going, becoming more stable and more profitable than ever.

Zimbabwe, DRC, Angola, South Africa, Ghana: the Ferrante are spread all over Africa’s most important diamond centres.

The Ferrante must also feel safe in regards to the Italian Justice. Antonino is jailed, awaiting trail, but they cannot be labelled as mafiosi, they have never been investigated for that, and South Africa does not recognise such a crime.

Italian history teaches the Mafia grew stronger because it learned how to go global, how to become a capitalist venture while not losing its cultural roots and its criminal strongholds. The Cosa Nostra is ruthless at home, controlling the Island of Sicily through extortion, corruption and violence and yet makes wide use of white-collars abroad, from the Italian peninsula to New York, from Germany to Africa. Its power comes from an army of people serving the aim, and because family ties are mostly regarded as sacred. Even if set apart from continents and years of silence, a Sicilian family might always be called upon for assistance. Whether to provide it, is a matter of choice. And the Ferrante’s decision to embark on a venture with Antonino Messicati Vitale, a convicted mafia boss, raises questions. Both Pina and Salvatore Ferrante refused answering to IRPI questions, which were exploring the issue. Pina only commented “I am not in the diamond industry”.

Antonino’s money is filthy, earned through drugs, extortion and violence but thanks to his family ties he can ensure Cosa Nostra’s hand in the diamond trade remains firmly clenched. For him, the family connection means he can exploit Africa’s resources following a new type of colonialism. Gangster capitalism is fascinating and profitable to others because of the ease and speed in which capital can be injected, laundered, and tripled in an endless circuit.

Unfortunately, the entry of Mafioso, directly or indirectly, into the regions still emerging from apartheid, civil war and poverty far-reaching and unhappy consequences. For every already rich Liebenberg allegedly swindled out of his wealth, there are thousands of ordinary people who do not benefit from the properly taxed and distributed wealth their countries offer the world.

The majority of the documents used for this story have been uploaded by IRPI-ANCIR and can be now read on sourceAFRICA.

Joint by-line Giulio Rubino, Cecilia Anesi

Additional reporting by Khadija Sharife for Zimbabwe, Atanas Tchobanov for Bulgaria

Infographics by Davide Mancino

Data analysis Stefano Gurciullo

This project is produced by journalism centres IRPI, ANCIR, CORRECTIV with QUATTROQUATTI and made possible by IDR Grant and Journalismfund.